The India Club was not chic or fancy. It was a no-frills restaurant, serving delicious lamb bhuna and fish curry.

Joseph Mitchell, the American journalist and writer, elevated the art of writing about the demise of favourite restaurants which are now lost to the relentless forces of development. He passionately believed that the soul of his cherished city, New York, could be found somewhere, it would be in the backstreet eating houses.

In the wistful echo of Mitchell’s spirits, I cannot help but lament the rude health of cherished London establishments, each bearing its own unique tapestry of fondness.

Whether it is the announcement of the closure of the two-Michelin star restaurant Le Gavroche, a pioneer of the food scene for more than five decades, or the closing down of the legendary Banner’s café in Crouch End after three-long decades which also drew the enigmatic Bob Dylan, it felt the gems from long-ago London, untouched, unreconstituted and ungentrified, were falling apart, each at a time, as the long days of summer start to fade away.

However, my heart will always resonate most profoundly with the permanent closure of the India Club – the capital’s most singular restaurant and bar – an institution to my mind that belongs to a different category.

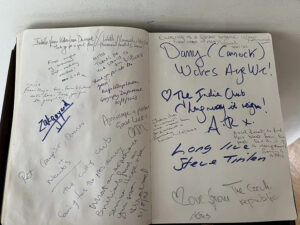

The comments on the visitor’s book says it all.

Ever since my time in London, the India Club has been my go-to place: a comfort during demanding days, celebrating birthdays, personal occasions or cultivating sublime friendships from all walks of life, especially concerning or linked to South Asia.

India Club- A Sense of Belonging

As a frequent visitor of the Club, the space gave me a sense of belonging: a natural human instinct as a South Asian migrant. I never imagined that the place where I once found space, comprehension and calmness amidst the hustling culture of London to contemplate pressing issues while holding a glass of Mango Lassi (which seldom they run out of) would reject me twice during its final phase: a reminder of the luxury I had taken for granted during my formal days at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

As a frequent visitor of the Club, the space gave me a sense of belonging: a natural human instinct as a South Asian migrant.

While the closing of the Club was long anticipated, if not too far, the very soon dreadful announcement from the Marker family – who have run the club for almost 30 years with utmost dedication and commitment – induced a flood of emotions, including shock and sadness, as it often happens when one tries to brush off the reality under the carpet, despite knowing it entirely. It was indeed a long silence before a final adieu, as the long days of summer started to fade as a distant memory.

Yet, the final days have been a hotter ticket, busiest I have ever seen, with its well wishers and loyalists, some even in their late 90s with more enthusiasm and sadness than one can expect, coming together to bid their final farewells and reminiscing their bygone “golden days.”

For more than seven decades, it stood as a bustling epicentre for the Indo-British groups, forged in the wake of Indian independence and the tumultuous partition era, including the Calcutta Rowing Club, Goan Association and the Curry Club.

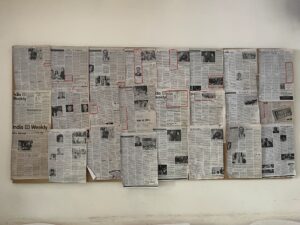

Within its walls, photographs of Dadabhai Naoroji – the first Indian MP in the UK – and other dignitaries, including former defence minister of India VK Krishna Menon, compounded with other Indian scenes hung, which attracted the likes of the Indian Journalist Association, Indian Workers Association, and Indian Socialist Group of Britain converged as a vibrant hub for their myriad events and endeavours.

Yet, the final days have been a hotter ticket, the busiest I have ever seen, with its well-wishers and loyalists, some even in their late 90s with more enthusiasm and sadness than one can expect, coming together to bid their final farewells and reminiscing their bygone “golden days.” From time to time, depending on how quickly the tables were cleared, a line sprawled almost an hour before the opening of the Club, with more than two hours waiting in the evening out onto the sidewalk – a surge drawn by nostalgia, as a member of the Marker family told me.

Situated in the heart of London’s Strand across the road straddled between Fleet Street and the Royal Court of Justice, it attracted a cosmopolitan clientele of employees from the Indian House, journalists, lawyers, lecturers and students from the London School of Economics and King’s College, next door.

However, for anyone who has not been there, describing the place is difficult. Situated in the heart of London’s Strand across the road straddled between Fleet Street and the Royal Court of Justice, it attracted a cosmopolitan clientele of employees from the Indian House, journalists, lawyers, lecturers and students from the London School of Economics and King’s College, next door. While the building wears a weary look and the decor frozen in time, giving it a timeless quality, if a restaurant was ever a cult, the India Club is it.

Yet, the India Club was not chic or fancy. It was a no-frills restaurant, serving delicious lamb bhuna (roast) and fish curry passionately to its customers with one purpose: to further ‘Indo-British friendship.’

And in many myriad ways, it achieved its motto. It is only telling that the closing of the India Club comes at a time when Britain is desperate to deepen its ties with India, more than ever.

The India Club was not chic or fancy. It was a no-frills restaurant.

But the Club has been resilient all these years. Despite the Club increasing its prices with the impact of the cost of living crisis, the prices continued to be fairly decent than any other Indian restaurant in central.

In 2019, the club proudly labelled itself a community treasure when it hosted a National Trust exhibition on its premises. As a testament to its historical significance, the British Library now houses oral histories from this exhibition, among which is the story of David, the son of the legendary waiter Joseph.

While we enjoyed our Paneer Butter Masala.

During my initial visits to the Club, I took my friend from Brazil to the club – who has a fine sense of dining and cultural understanding. “Is that Mahatma Gandhi?” she asked, as she pointed to the painting on the wall while eating Paneer Butter Masala, which continued to become our go-to dish at the club. “We should come here often,” she smilingly said. Which we indeed did.

And as the sun set on 17 September, an era has come to an end.

During the final week of the Club, we celebrated our second London anniversary in the Club together. Unlike whenever we promised to be at the Club soon without any kind of waiting, this time we waited for two hours to get the table (we got lucky to get the same table which we often used to dine at!) and unfortunately, there won’t be any more evenings like those.

And as the sun set on September 17, an era has come to an end. The India Club was one of the lasting institutions that played a pivotal role in the narratives of diasporas and independence movements of the nation. Similarly, I could think of the Polish Club, overlooking Hyde Park with the history of the Free Polish forces and their base in London. The Irish Club too, located in the opulent Eaton Square, exuded significance.

Currently, the India Club is looking for an alternative space nearby. However, even if that materialises in all fairness, will it be able to recreate the spirits of the institution in a new settling? Scepticism only abounds.

Currently, the India Club is looking for an alternative space nearby. However, even if that materialises in all fairness, will it be able to recreate the spirits of the institution in a new settling? Scepticism only abounds.

Cities are ever-evolving landscapes, forever in motion. At a time like this, when cultural vandalism is all pervasive, what does one do? I chose to cling to memories, more than ever, that acted as a hub of intellectual exchanges and fostering of progressive ideas.

Kalrav Joshi is a London-based journalist-writer. An alumnus of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), he writes on politics, culture, technology and climate.

Courtesy : “The Quint”; 26 September 2023

Photo courtesy : Kalrav Joshi

![]()