Two intellectual heroes with not a trace of pomposity and a fine sense of humour

In the past decade, I have often visited Cambridge, Massachusetts, and come to like it enormously. The town has fine cafes and bookshops and — as the home of Harvard and MIT—a greater concentration of intellectual talent than any other place in the world. The best time to visit it is in the fall, when the air is crisp and the sky cloudless, and the colours are beginning to change.

I spent the last week of October in Cambridge. I ate at some nice places, rummaged through the shelves and cartons in the Harvard and Raven Bookstores, walked through the streets, met some old friends and made some new ones. I also made a trip to Walden Pond, taking a long parikrama around it, observing the other worshippers, young and old, as well as the glorious foliage that surrounds these holy waters.

For me, among the attractions of Cambridge, Massachusetts, is that it is home to two scholars I enormously admire. One is the great historian of modern China, Roderick MacFarquhar. Rod (as I call him) is of Scottish extraction. He was born in 1930 in Lahore, where his father was a colonial civil servant. He was sent to boarding school in Scotland, and then went up to Oxford. On graduating, he became a journalist, covering Jawaharlal Nehru’s funeral for the BBC and Mao’s Cultural Revolution for The Economist. He then served a term in the UK Parliament as a Labour MP.

Roderick Macfarquhar

Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies

In 1960, while still a journalist, Rod MacFarquhar had founded The China Quarterly, which quickly became the leading English-language journal on contemporary China. Before entering politics, the editor had himself written several books on China. After he failed to win re-election to Parliament, Rod chose not to return to journalism but to become an academic instead. In the 1980s, he was appointed to a professorship at Harvard University and, later, became a much admired head of its Government Department. In between his teaching and administrative duties, he authored three landmark volumes on the origins of the Cultural Revolution.

American universities have no retirement age for their professors. Some carry on teaching into their eighties and even into their nineties, determined to have a say in new appointments and curriculum changes even when manifestly out of touch. Like most politicians, most academics also do not know when to retire. Rod MacFarquhar was different. He chose to vacate his prestigious named chair when people would ask ‘Why?’ rather than ‘Why Not?’. A young friend of mine took one of his last classes, a seminar on ‘Political Leadership’, which had its students absolutely enthralled.

In retirement, Rod MacFarquhar continues to write the odd essay in The New York Review of Books, to attend seminars and answer queries from younger academics (when asked). But unlike most other academics and unlike almost all politicians, he has no desire to cling on to the vestiges of the power and the status that past accomplishments have awarded him.

Rod MacFarquhar has lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, for the past three decades. Another scholar I venerate moved there more recently. E.S. (Enuga) Reddy was born in Nellore in 1924; after taking a first degree in Madras (where he was active in student politics), he went to New York for further studies. Thereafter, he joined the United Nations, where he worked for 35 years, ending as Assistant Secretary-General.

Mr Reddy had many different assignments in the UN. However, he was best known for steering the organization’s Special Committee against Apartheid. From the early 1960s to the mid 1980s, he catalyzed world opinion against the racist regime in South Africa. After he retired, he continued the campaign in his personal capacity. When apartheid finally fell, Mr Reddy visited South Africa where he was received like the hero he was, and decorated with a high State honour. Not long afterwards, in Mumbai, I met an activist from Durban who had spent many years in exile. When I mentioned Mr Reddy’s name, he instinctively stood up as a mark of the respect that so many ordinary South Africans have for this extraordinary Indian, and which must surely mean more to the man than the Order of the Companions of O.R. Tambo that he also possesses.

While working on South Africa, Mr Reddy developed a serious scholarly interest in Gandhi. He now has the largest collection of articles and clippings on the subject outside of the Sabarmati Ashram. These he shares freely with scholars of all nationalities and countless books written by others have been made possible by his generosity.

Mr Reddy and his Turkish wife (a translator of the poet, Nazim Hikmet) lived for more than 50 years in Manhattan. However, a couple of years ago, their daughter persuaded them to move to Cambridge where she was herself based. It was in this town that I saw the Reddys last month, in their new apartment off Western Avenue. We spoke, as always, mostly of the Mahatma.

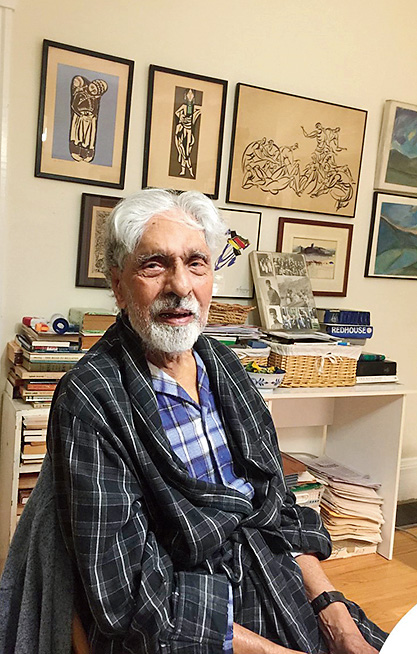

Enuga Sreenivasulu Reddy

On this last visit, I also saw Rod MacFarquhar in his apartment on Memorial Drive. As I entered, Rod paid me an unexpected compliment; I was, he said, the third Indian he had known who always arrived on time. (I asked for the names of the others; they turned out to be the patriot and liberal parliamentarian, the late Minoo Masani; and the maverick economist-turned-hardline Hindutvavadi, Subramanian Swamy.)

Note that I call one man by his first name and the other by a respectful prefix. This is because I got to know Rod in the informal, relaxed world of the American academy; whereas Mr Reddy is my father’s age and has been, in terms of his influence on my own work on Gandhi, a father-figure.

Roderick MacFarquhar and Enuga Reddy do not know one another. It is very likely that they do not know of each other. Yet, in this writer’s mind, they make for a natural pairing. Both have made major contributions to scholarship and to public life. Both have nurtured institutions and mentored many talented individuals. Both have strong roots in their native country but are greatly admired in a country not their own: China in the case of Roderick MacFarquhar, South Africa in the case of E.S. Reddy. And yet both made their home and carried out their profession in a third country altogether: the United States of America.

Rod and Mr Reddy are also united by attributes of personal character. In their prime, both wore their learning as well as their professional distinction lightly. Now, in retirement, they absolutely do not crave or miss the power or fame they once possessed. Neither has a trace of pomposity; both have a fine sense of humour (often aimed at themselves). Both are generous with their time and their resources; Mr Reddy has donated rare South African materials to Yale and rare Gandhi materials to the Nehru Memorial Museum & Library, while Rod is keen to donate his great library of Chinese materials to a university in India.

While in Cambridge in late October, I enjoyed my time in the bookstores around Harvard Square and my walk around Walden Pond. But the highlight of my visit was the darshans I had and the conversations I conducted with Roderick MacFarquhar and Enuga Reddy, two of my personal heroes.

courtesy : "The Telegraph", 10 November 2018

![]()