Lecture given in Marathi at the Marathi Poetry Since Independence Seminar

the Department of Marathi, M. S. University of Baroda, 1990

1.

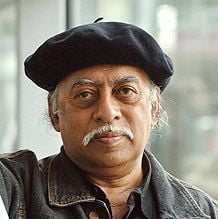

Although following Bal Sitaram Mardhekar after he set the trend of poetry with modern sensibility in Marathi language there were several poets making meaningless repetition of him, Dilip Purushottam Chitre and Arun Kolatkar were amongst those very few leading poets who retained their unique identity and created poetry with individual style. Their contribution to Marathi poetry in terms of content and style is so immense that not only for the four decades of Mardhekar but also deserve an important place in the whole tradition of Marathi poetry after Tukaram.

That like their contemporary poets Sadanand Rege, Grace, Arati Prabhu, Namdeo Dhasal and Narayan Surve, Chitre and Kolatkar too created a space for their sensibility and an independent readership in Marathi language. Although their poetry is loaded with the cultural references to Maharashtra like Dnyaneshwar, Tukaram, Jejuri, and Panhala, the Indian and Western ideologies emerged outside Maharashtra have also been assimilated in it and they are quite clear. Both these poets are the best examples of the influence of two hundred years encounter and hybridization of English and Marathi after Mardhekar. Mardhekar, Chitre and Kolatkar are the most significant Marathi poets of twentieth century who assimilated the Western literature and style but never forgot their native poetic tradition.

That like their contemporary poets Sadanand Rege, Grace, Arati Prabhu, Namdeo Dhasal and Narayan Surve, Chitre and Kolatkar too created a space for their sensibility and an independent readership in Marathi language. Although their poetry is loaded with the cultural references to Maharashtra like Dnyaneshwar, Tukaram, Jejuri, and Panhala, the Indian and Western ideologies emerged outside Maharashtra have also been assimilated in it and they are quite clear. Both these poets are the best examples of the influence of two hundred years encounter and hybridization of English and Marathi after Mardhekar. Mardhekar, Chitre and Kolatkar are the most significant Marathi poets of twentieth century who assimilated the Western literature and style but never forgot their native poetic tradition.

Chitre and Kolatkar are different from others in the field of Marathi poetry for one more reason that though both of them have proved their mastery in Marathi they continued writing poetry with all sincerity in English as well. Here certain issues regarding the Marathi criticism of poetry and history of Marathi literature are discussed with reference to their English poems.

2.

The contribution of Chitre and Kolatkar to English poetry is so substantial that even if they could not have written anything in Marathi yet they would have retained their position among Indian poets. Along with the publication of Marathi poems in Satyakatha Chitre was writing several articles, reviews etc. for English literary magazine Quest. After few years of the publication of his first anthology of Marathi poems, an anthology of translation of his Marathi poems into English was also brought out as An Anthology of Marathi Poetry (1945-1965).Including his Ambulance Ride, his long narrative poem which was previously published in limited number of copies in 1972, an anthology of his English poems Travelling in a Cage was brought out in 1980. Apart from this anthology, there are large number of poems he read outside Maharashtra on different occasions and published in journals. In 1991, his translation of Tukaram's poetry into English entitled as Says Tuka was published. The publication of his translation of Amrutanubhava in English is awaited.

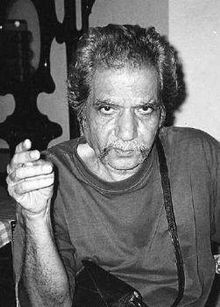

Kolatkar's early poems were published in literary magazines and before the publication of Marathi anthology of his poems Arun Kolatkarchya Kavita in 1976; he had established his reputation as the most important poet in Marathi. Jejuri, his anthology in English, brought him Commonwealth Poetry Prize and his poetry received recognition at international level in the field of English literature. That like Chitre, Kolatkar had also translated poems from Marathi into English and published in several other books including an anthology edited by Chitre in 1965.

3.

It was in early nineteenth century the young teachers in Hindu College of Kolkata started the practice of using English to describe Indian scenario in poetry. With the inclusion of English language and literature in the curriculum of schools and colleges, this tendency got spread outside Kolkata too. Due to the English translation of his works as Rabindranath Tagore received the Nobel Prize for literature in the early twentieth century, the contemporary poetry was profusely translated from Indian languages into English. Emergence of modernity in literature in the post-Independence period stylistically breathed a fresh air into Indian English poetry. Recognition of English as an official language of India by Indian Constitution boosted up the tendency to prefer English language for creative writing though the writers lived in India. In the history of Indian poetry in English spanning over two hundred years the names of five to six poets are inevitably mentioned and after the publication of Jejuri in 1976 Arun Kolatkar is one of them. Moreover, Chitre's reputation has also been increasing in this canon. Publication of Nissim Ezekiel's anthology of poems A Time to Change (1952) has been considered as the beginning of modernity in Indian English poetry. During these four decades Ezekiel, Ramanujan, Kolatkar and Jayant Mahapatra are considered to have contributed substantially to this kind of poetry. Their poems are included in the university curriculum of several countries. And wherever English education has reached, these poets are known, may be at the introductory level, to the academic world of teachers and students. In recent times, Chitre's name is also getting associated with other prominent poets. Therefore, these two important Marathi poets of ours could have certainly been recognized as the significant poets in Indian English and therefore, significant Marathi poets too.

It was in early nineteenth century the young teachers in Hindu College of Kolkata started the practice of using English to describe Indian scenario in poetry. With the inclusion of English language and literature in the curriculum of schools and colleges, this tendency got spread outside Kolkata too. Due to the English translation of his works as Rabindranath Tagore received the Nobel Prize for literature in the early twentieth century, the contemporary poetry was profusely translated from Indian languages into English. Emergence of modernity in literature in the post-Independence period stylistically breathed a fresh air into Indian English poetry. Recognition of English as an official language of India by Indian Constitution boosted up the tendency to prefer English language for creative writing though the writers lived in India. In the history of Indian poetry in English spanning over two hundred years the names of five to six poets are inevitably mentioned and after the publication of Jejuri in 1976 Arun Kolatkar is one of them. Moreover, Chitre's reputation has also been increasing in this canon. Publication of Nissim Ezekiel's anthology of poems A Time to Change (1952) has been considered as the beginning of modernity in Indian English poetry. During these four decades Ezekiel, Ramanujan, Kolatkar and Jayant Mahapatra are considered to have contributed substantially to this kind of poetry. Their poems are included in the university curriculum of several countries. And wherever English education has reached, these poets are known, may be at the introductory level, to the academic world of teachers and students. In recent times, Chitre's name is also getting associated with other prominent poets. Therefore, these two important Marathi poets of ours could have certainly been recognized as the significant poets in Indian English and therefore, significant Marathi poets too.

4.

Although it is not appropriate, the creative writing of Marathi writers in English is charged for disloyalty with Marathi on two grounds: British ruled over India for around two hundred years in an extremely unjust manner and natives have to fight to free themselves from it and the spread of English has been shrinking the growth of Marathi. In India before the British rule and the spread of English, it was a common practice to write poetry in two or more than two languages. To use Sanskrit and Prakrit in the same literary work, to use the content and references from Sanskrit to write in Prakrit, to compose Puranic narrative on the Bible and Christianity, to compose poetry about Hindu gods and goddesses in Persian and Arabic, to translate Mahabharata and Ramayana into Persian and Turkey, to write books about Gita and Upanishadas in indigenous languages or to write in Sanskrit about the stories in indigenous tradition were the common practices found in abundance in ancient Indian literature. Dandin had developed his literary theory and linguistic narratives on the basis of such practices. It is on record that Vishwanatha composed a poem using sixteen languages. Along with Marathi Namdeo had composed the poems in quite a few dialects in Northern part of India. It is also a well-known fact that Jaydeva's Geetgovind was originally composed in Bengali and then in Sanskrit.

Therefore, Chitre and Kolatkar's Marathi- English compositions should be viewed in the context of vast historical context of bilingualism in literature. The tensions that existed between the relations of Sanskrit and Prakrit or Desi and Persian or Arabic languages exist in the relationship between Indian languages and English in contemporary time. If we are aware of this historical context, we could never forget that Chitre and Kolatkar belong to a native tradition as well as are genuinely modern poets and their Marathi and English poetry are inseparable from each other. Moreover, limitations in understanding their poetry causing from reading within the context of Marathi can also be avoided.

5.

It is not sufficient to note that Chitre and Kolatkar are bilingual poets. Because Chitre is a painter and has worked in film industry too. He has also ventured into different fields of creativity like short stories, literary essays and thought provoking prose, and plays. Kolatkar is also a painter and a graphic artist. Now he was trying his hand at prose. It would also be possible to say that while translating Chitre and Kolatkar write in a language other than Marathi and English.

It is assumed that to translate means to create an unprecedented linguistic texture and canvas in a target language. In Bhalchandra Nemade's theory of translation, there is a clear distinction between the language of translation and the dialect created by translation. If we agree with this principle that during the passage of time the dialect created by translation creates a space for itself in the main stream of language of translation and causes new dimensions to the meaning in the main stream, we have to accept that Chitre and Kolatkar's translated works represent a new language which is at the border of Marathi and English and constantly growing. Chitre himself has called this new topography of language as a bridge. In his English article on translation Life on a Bridge, he has explained the ethics, rules and principles of this new topography of language:

I have been working in a haunted workshop rattled and shaken by the spirits of other

literatures unknown to my ancestors. In fact, unknown spirits claim to be my literary

ancestors clamouring for recognition. Europe has already haunted my house. A larger Indian tradition besieges it too, and this tradition was sometimes perceived as such by the Europeans first. Even as an independent practicing poet, I live in the post-modern world transformed by translation. this is my predicament as a writer. I have to build a bridge within myself between India and Europe or else I become a fragmented person. (The Bombay Literary Review, 1989:I, p: 14)

Of which topographies of language, spread across both the ends of a bridge, a citizenship would be conferred on such poets who live on the bridge of translation to avoid the fragmentation of identity. In Marathi and English criticism efforts have been made to recognize their Marathi poetry and discard English poetry as mediocre. Such criticism is based on the assumption that Chitre's mother tongue is Marathi and the structure and development of world of imagination is possible genuinely only in a mother tongue. The foundation of this criticism is the principle that poetry is highly personal expression of poet's insights and the origin of poetry lies in the deepest terrains of his conscience and therefore, it is impossible to create a good poem in a language "acquired" after childhood. It is also assumed in such a criticism that there is a certain Marathi-content that can be expressed only in Marathi and English-content in English and therefore, by turning languages upside down language-specific content cannot be expressed. Chitre and Kolatkar compel us to re-examine these principles and positions.

6.

Chitre was born and brought up in Baroda. His anthology Travelling in a Cage contains a poem The Felling of a Banyan tree about this experience. It it usual themes of English poetry such as diaspora or rootlessness or the pain caused by the forced migration could be seen. And a neutral view of one's own father which is a prevailing tone in English poetry could also be seen in it. But along with it his contemplation about death, fear of misinterpretation of emotions, and the images constantly stressing instability evident in his Marathi poetry are found in English poetry too. Moreover, it contains the domestic references to Marathi family like the images of trees of drumsticks, Neem and Audumber planted due to Marathi culture, grandmother's tales, and the circles of mythological stories of two hundred years around the banyan tree:

My father told the tenants to leave

who lived in the houses surrounding

our house on the hill

One by one the swtructures were demolished

only our own house remained and the trees

Trees are sacred my grandmother used to say

Felling them is a crime but he massacred them all

The sheoga, the oudumber, the neem were all cut down

But the huge banyan tree stood like a problem

Whose roots lay deeper than all our lives

My father ordered it tom be removed.

All these Desi references keep surfacing in Chitre's English poems several times. On the contrary, in his Marathi poems the traditions of several countries including Greece, Rome, England, France, Russia, and South America are mentioned. Even some of the themes, which prevail only in English also appear in his poems. It makes clear that to state Chitre uses English for certain themes and Marathi for certain themes would be unrealistic.

Kolatkar's Marathi poem uses surrealism profusely. His Marathi poem Takta based on Marathi alphabets appears different due to surrealism. Kolatkar's cynical humour in Marathi is very much in consonance with English and behind his method of employing images also had a long tradition of Western Imagism. In sharp contrast to this, Khandoba, different deities, and different myths known in every household of Maharashtra used in Jejuri as its content. The flowers mentioned in Jejuri are no other than Marigold:

Chaitanya

Come off it

Said Chaitanya to a stone

in stone language

Wipe the red paint off your face

I dont think the colour suits you

I mean what's wrong

with being just a plain stone

I'll still bring you flowers

You like the flowers of Zendu

don't you

I like them too

Moreover, the stones in Kolatkar's English version of Jejuri could be seen in mountains and valleys of Maharashtra and known to all for disowning their status as a stone and assuming the role of God at any time:

A Scratch

What is God

and what is stone

the dividing line

if it exists

is very thin

at Jejuri

and every other stone

is God or his cousin

there is no crop

other than God

and God is harvested here

around the year

and round the clock

out of the bad craft

and of the hard rock

that giant hunk of a rock

the size of a bedroom

is Khandoba's wife turned to stone

the crack that runs right across

is the scar from his broad sword

he struck her down with

once in a fit of rage

scratch a rock

and a legend springs

If a Marathi-specific content and English-specific content can maintain a close relationship with Marathi and English poems, the relationship between the streams of sensibilities in poetry and mother tongue are to be reassessed.

7.

The misconception of regarding literary creativity as a monolingual activity- English literature in English, French literature in French, Tamil literature in Tamil etc. – is an outcome of acceding to distorted history of literature. In India, traditionally, history of literature meant literary legacy stored in memory. Before implanting the concept that literature is a subject of teaching, and it could be a thing to be transferred from one generation to another through Western educational method in India, literature was considered as a cultural practice and it was open for all to participate and contribute. The very concept of Sahitya indicates the same. In this celebration of goddess of literature there was no discrimination such as canon and para-literature, mainstream and parallel, original and distorted. It was due to this liberal approach Eknath, Tukaram, Namdeo spread their roots and became more respectable than Vamana and Ramdasa in Maharashtra. As the history of English literature reached to us during British rule, we too restructured the history of Marathi literature in a grossly loose manner. Imitation of British model resulted into a superficial compartments of literature as Ancient, Middle Ages and Modern. On the same grounds, upper storey of literature and lower storey of folk-literature were also constructed. And we developed a habit to insist on painting all those sections with the same colour of the same language. Multilingual tradition of writing in India was ignored. The Gujarathi-Marathi speaking followers of Mahanubhava sect have paved the way for writing in a symbolic language. Several saint-poets had their compositions in Marathi-Hindi, Marathi-Punjabi, Marathi- Kannada, and Marathi- Konkani. However, from mid-nineteenth century we kept aside the rich treasure of multi-dialectic, multilingual poems and tales from the history of literature designed only for teaching in schools and colleges; and recognized the literature written only in Marathi or mainstream Marathi.

Slowly and gradually, such histories of literature espouse monolingual ways of literary taste and criticism. That strengthens the theories of mother tongue originated in European linguistics.

Due to the imitation of history of English literature, the concept of "ages in literature" got imposed on us and we started to assume that something great emerges in each age of literature than the previous one and we even began to insist on happening so in each age.

8.

Compared to the field of literature Music has remained "Indian" to a great extent. It does not mean that West did not influence it but the method of training in music has remained traditional largely. The concept of 'lineage' has survived against the concept of 'age' in it. The style of singing is not judged on the basis of its age but the Gharana or lineage. Actually, this concept can be useful in the field of literature to a great extent in India. As several Gharanas or lineages exist in the same age, different Gharanas of writing also exist. Some of the Gharanas are monolingual, some of them are multilingual and some of them are translationists.

Finally, if literature is an activity of works of art created by the union of a word and creativity and in a country in which more than two or three languages are used even for routine life, creation of literature facing life in two or three or even more languages is inevitable.

The theories of mother tongue and its influence on human psyche originated during the emergence of European nationalism and European colonialism. Therefore, it would not be appropriate to impose them on the histories of literatures of all languages in the world as universal truths. The concepts of First language and Second language may be inevitable in monolingual cultures and societies during the process of language acquisition but considering them as universal truths created obstacles in the theoretical progress of the linguist of Chomsky's eminence. But those are the issues for Chomsky and others. As far as we are concerned, some of the weaknesses of the history of Marathi literature become evident in the context of Chitre and Kolatkar's English poetry.

In contemporary history of Marathi literature Chitre and Kolatkar are primarily considered as Marathi and then English poets, and therefore, their creativity has not been explained from a proper perspective. Moreover, due to the accidental similarity of the periods of their birthdates from Narayan Surve, Dhasal, Chitre to Kolatkar are pushed into the same age of literature. Consequently, our understanding of modern Marathi poetry has remained weak. And the most important limitation is defining Marathi poem as "a poem written only in Marathi" which cannot accommodate in its scanty cover of history of literature the diverse and active shades of meanings Marathi and other dialects of Marathi and linguistic regions functioning on the vast canvas of translations of Marathi-Sanskrit, Marathi-Persian/ Urdu/ Hindi, and Marathi-English. The success of Chitre and Kolatkar's poetry lies in creating an awareness of these limitations.

—————————————————————-

(Translated from the Marathi original by Dilip Chavan)

• The article is drawn from the Marathi and English collection of articles Ekun Dilip Chitre. We gratefully acknowledge the courtesy of Mrs. Vijaya Chitre.

![]()

A broad-brush history of the last thousand years for the subcontinent that we now recognize A as India, whatever else it may or may not choose to recall, will look deficient if it does not mention the emergence of the modern Indian languages, the bhashas. Such a history is bound to talk of our transition from the feudal economy and political order to industrial economy and democracy. It will no doubt devote space to narrating the colonial experience, the clash between tradition and modernity and the shift from conventional rural forms of sense and sentiment to semi-urban order of civics and ethics. But no history of India over the last millennia can be conceived or completed without pointing to the birth and the pervasive spread of the bhashas.

A broad-brush history of the last thousand years for the subcontinent that we now recognize A as India, whatever else it may or may not choose to recall, will look deficient if it does not mention the emergence of the modern Indian languages, the bhashas. Such a history is bound to talk of our transition from the feudal economy and political order to industrial economy and democracy. It will no doubt devote space to narrating the colonial experience, the clash between tradition and modernity and the shift from conventional rural forms of sense and sentiment to semi-urban order of civics and ethics. But no history of India over the last millennia can be conceived or completed without pointing to the birth and the pervasive spread of the bhashas.