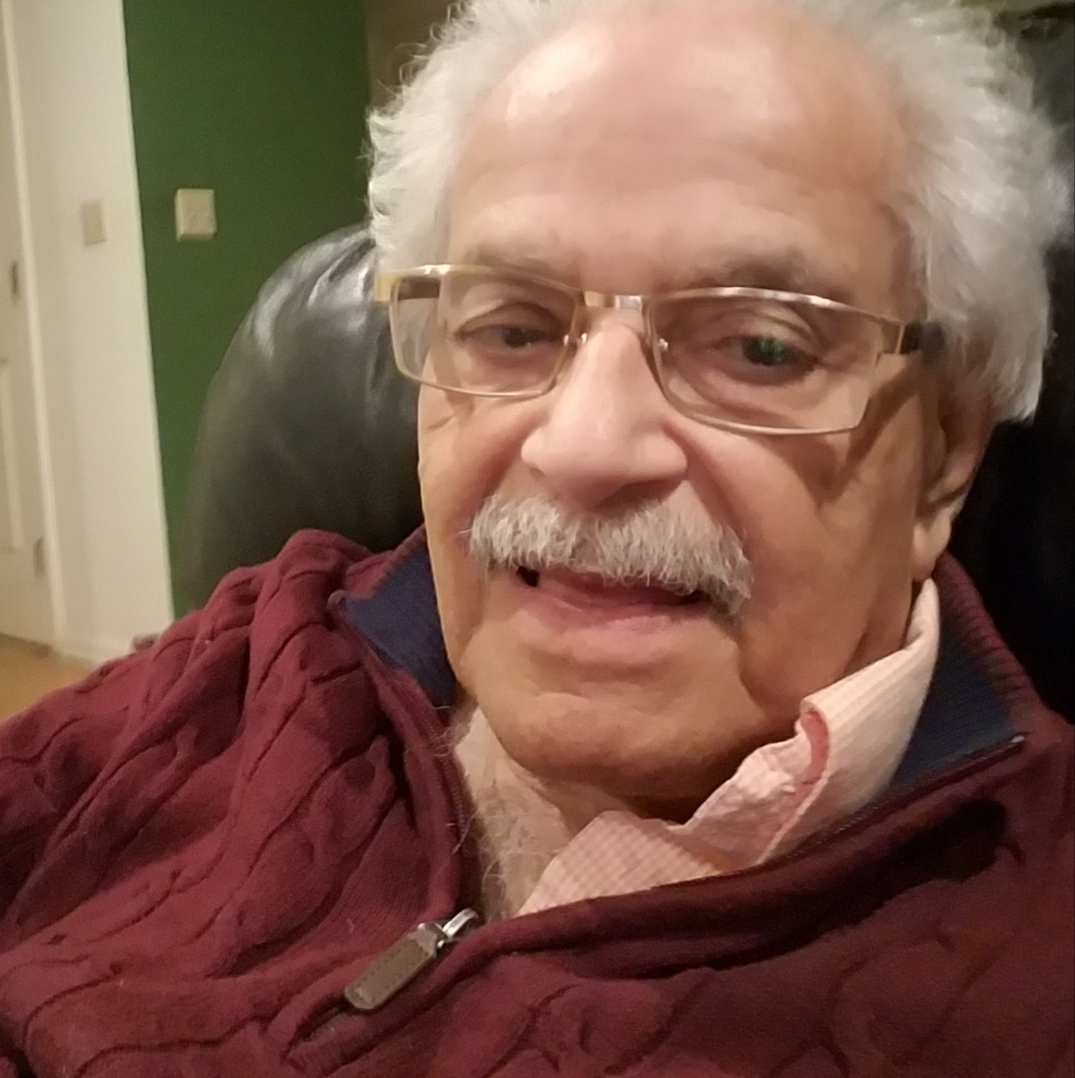

An Eulogy for Navin Jarecha, February 23, 2022

Franklin Memorial Park, New Brunswick, New Jersey

હતો ભટકતો હતાશ નિજ દેશ દુઃખે ભર્યો,

તમે નવીન દેશથી પકડી હાથ તાર્યો મને.

This is how I dedicated my first book of poems, appropriately called America, America to Navin Jarecha. Loosely translated it means:

Hopeless and unhappy,

Lost I was in my home land,

You brought me to the Promised Land,

And saved my life.

It is because of him and him alone that I stand before you today. He was responsible for my coming to America. He has had the largest influence on my professional life for the past sixty years.

I first met Jarecha in 1957. We always addressed each other by our last names. I was Gandhi to him and he was Jarecha to me. We both attended Sydenham College in Mumbai. He was senior to me in college. We both were amateur poets. It is poetry that brought us together. Soon after joining the college, I noticed that there was a Gujarati literary wall where students could post poetry and other writings. Everything on the wall was handwritten.

I first met Jarecha in 1957. We always addressed each other by our last names. I was Gandhi to him and he was Jarecha to me. We both attended Sydenham College in Mumbai. He was senior to me in college. We both were amateur poets. It is poetry that brought us together. Soon after joining the college, I noticed that there was a Gujarati literary wall where students could post poetry and other writings. Everything on the wall was handwritten.

After a few months, I gathered enough courage to approach a student who was posting new material on the wall and introduce myself. “I write poetry and would like to put my poems on the wall. How do I do it?” “Give me your poems,” he replied. “I will put them up. I am the editor. My name is Navin Jarecha.” That was how I first met him. I have always marveled how that chance encounter changed my life profoundly for the better and forever!

We quickly bonded. Though Jarecha also came from the provinces like me, he had none of my inhibitions. Always sure of himself, he moved about the college halls freely and even dropped unannounced into the office of professors. He exuded confidence. He dressed smartly in a traditional Indian kafani lengha dress that was always ironed and, on his feet, wore fancy chappals. At lunchtime we would share our poems and I would share his lunch! He was lodging with his sister in a distant Mumbai suburb. She would send him off daily with lunch tiffin.

Through Jarecha I met another student poet, Meghnad Bhatt who was the son of Harishchandra Bhatt, a distinguished Gujarati poet whose work I knew. The three of us became good friends and read each other’s poems daily. Jarecha and Bhatt played significant roles in my life. Jarecha brought me to the U.S. and Bhatt helped me get my first paying job. A phone call from Bhatt to a friend did the trick that a hundred job applications could not. Such were the vagaries of Mumbai’s job market during the 1960s.

When Jarecha went to the U.S. in 1960, I had hoped he would find me a way to get there. In fact, I went to Mumbai’s Ballard Pier to see him off. He could not afford to fly so he sailed in a cargo ship. I made my way to his ship’s cabin and took him aside. “Please, Jarecha,” I said, “do something, anything to help me get to the U.S.” As my frustrations in Mumbai mounted, I kept sending Jarecha letters asking about my coming to the U.S. He would write to me back saying that yes, he would help. He kept his promise, though it took some time.

Five years after he left for America, I received a telegram from Jarecha. He said that he had arranged for my admission to Atlanta University. “Start packing,” he wrote. “The fall semester is about to start.” I telegraphed back explaining my financial situation. I would need his help for paying everything—tuition, living expenses, the airline ticket and some additional money to send home to my family. Jarecha replied immediately that he had arranged for everything including the air travel through a grant from an educational foundation. Those were the glory days of higher education in America!

I felt immensely relieved. Suddenly I was free—free of all my troubles, my worries, hurts and humiliations that I had suffered in Mumbai. As I climbed the stairs to board the Air India plane bound for New York on that day in October, 1965, I murmured a famous Khalil Gibran line: “Then we left that sea to seek the greater sea!” And added, “thanks to Jarecha!”

I have remained grateful to him ever since for saving my life that would have been wasted in India. In this I was not alone. Truth be told, he has saved a few hundred such lives. Many people whom he helped brought their own relatives and friends to America in a chain migration that would have given Donald Trump a heart attack had he known about it.

Jarecha was my mentor during my college years in Mumbai and during all my days in Atlanta where we were together practically every day. Like an elder brother, he looked after me–took me shopping, to restaurants where I was working as a busboy and places where I needed to go. When I took my first job in Greensboro, North Carolina, he visited me there and made sure that I had settled down properly. He told me that he was just a phone call away.

His willingness to help extended to all without discrimnation –black and white, old and young, men and women. But he was particularly kind to Indian students who had come to Atlanta University. Some empty handed studnets would call him from the airport the day they landed and ask for a ride to the University. He was kind of a one man, one stop social service agency. His goodwill toward people around him was legendary.

Though he was good, indeed very good to others, he was not good to himself. Unfortunately, he did not take care of himself. Most of his adult life in America, he was a chain smoker. He was equally careless about his diet and other habits. Worse of all, he never cared about his finances. After I moved away from Atlanta, I used to chide him about his smoking and other poor habits.

He was a proud man and hesitated talking about his troubles, including his finances. He would simply laugh it all off. He would say, “Gandhi, God is great and He will take care of me.” I would say, “but God has billions of others to take care of.” His rejoinder would be, “well, I was good to people so they will be good to me.” Life did not turn out that way for him. Toward the end, he paid dearly for all his carelessness. It still puzzles me how such a smart man could be so cavalier about his health and naive about his finances.

Panna Naik and I had been talking with him regularly during the past few months, however, the last we saw him in person was at an Indian restaurant in New Jersey just a few weeks ago. He had to be driven there. This must have been quite galling for him since he always insisted on driving during our numerous trips far and near. He was always our designated driver! He took great pride in his driving skills. But now the doctor had advised him not to drive as his body had debilitated due to several ailments that had plagued him. He looked haggard and did not have much to say during our lunch. After lunch, we hugged and said goodbye to each other. That was the last we saw of him.

On our way back to Washington, Panna and I talked about Jarecha all the way–how good he was to us and to others and how we all collectively failed in taking care of him. I deeply regret it. But it is all too late now.

![]()