In his first Independence Day speech, “A Tryst with Destiny,” at the midnight hour on August 14, 1947, India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru famously asked his fellow citizens: “Whither do we go and what shall be our endeavor? To bring freedom and opportunity to the common man…to build up a prosperous, democratic and progressive nation, and to…ensure justice and fullness of life to every man and woman.” As I ponder on what would the Prime Minister of India say from ramparts of the Red Fort on August 15, 2047 at the completion of India’s first hundred years as a free and independent nation? I imagine he or she would say that we have travelled far, wide and long from the day when Pandit Nehru gave his now famous speech with ceiling fans furiously circling overhead in the parliament before a rapt audience of fellow freedom fighters.

In his first Independence Day speech, “A Tryst with Destiny,” at the midnight hour on August 14, 1947, India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru famously asked his fellow citizens: “Whither do we go and what shall be our endeavor? To bring freedom and opportunity to the common man…to build up a prosperous, democratic and progressive nation, and to…ensure justice and fullness of life to every man and woman.” As I ponder on what would the Prime Minister of India say from ramparts of the Red Fort on August 15, 2047 at the completion of India’s first hundred years as a free and independent nation? I imagine he or she would say that we have travelled far, wide and long from the day when Pandit Nehru gave his now famous speech with ceiling fans furiously circling overhead in the parliament before a rapt audience of fellow freedom fighters.

As I look ahead thirty years from now, at the end of first century of its independence, India would have still remained a free and integrated country despite its continental size and myriad of differences among its widely varied people. At the time of independence, however, imperialists in UK and elsewhere were quick to warn that an Independent India would not survive long. During fifties and sixties, there was no shortage of observers at home and abroad who ominously predicted that the country would soon disintegrate. Some even called it “an area of darkness,” and wrote it off. Despite all this foreboding, India has survived as a largely secular, liberal democracy while many countries that got their independence just about the same time have descended into periodic dictatorships, military rules, or worse, chaos. I am quite sure that India will celebrate centenary of its independence as the most populous, largely stable, and mostly secular democratic country in the world.

By the time the hundredth anniversary of its independence arrives, India would have made substantial progress toward reducing the crushing burden of poverty that has plagued Indian masses all through its modern history. By year 2047, I predict a globalized Indian economy buoyed by a vastly improved infrastructure, an integrated national market, and an expanding manufacturing sector that would draw rural masses to its vibrant metropolis and would provide them with a better life.

However, I also see two danger signs. First, thirty years from now, I see India most likely facing massive challenges of environmental degradation and air pollution unless drastic measures are taken now to protect environment and curb pollution. Second, its demographic dividend–the largest pool of young people ready to work in the world–could become a major liability if the economy does not produce enough jobs. If this expanding workforce–a million or more a month–is not gainfully employed, then I see India failing to achieve its full potential.

Despite resilience and resourcefulness of people of India, the country has been hamstrung for over a century by an obdurate and insensitive bureaucracy and a feudal framework of social and political institutions. This iron frame has to be reshaped because it has hindered India’s march towards a nation of Pandit Nehru’s vision on that day in 1947 when he said we had “a tryst of destiny.”

e.mail : natgandhi@yahoo.com

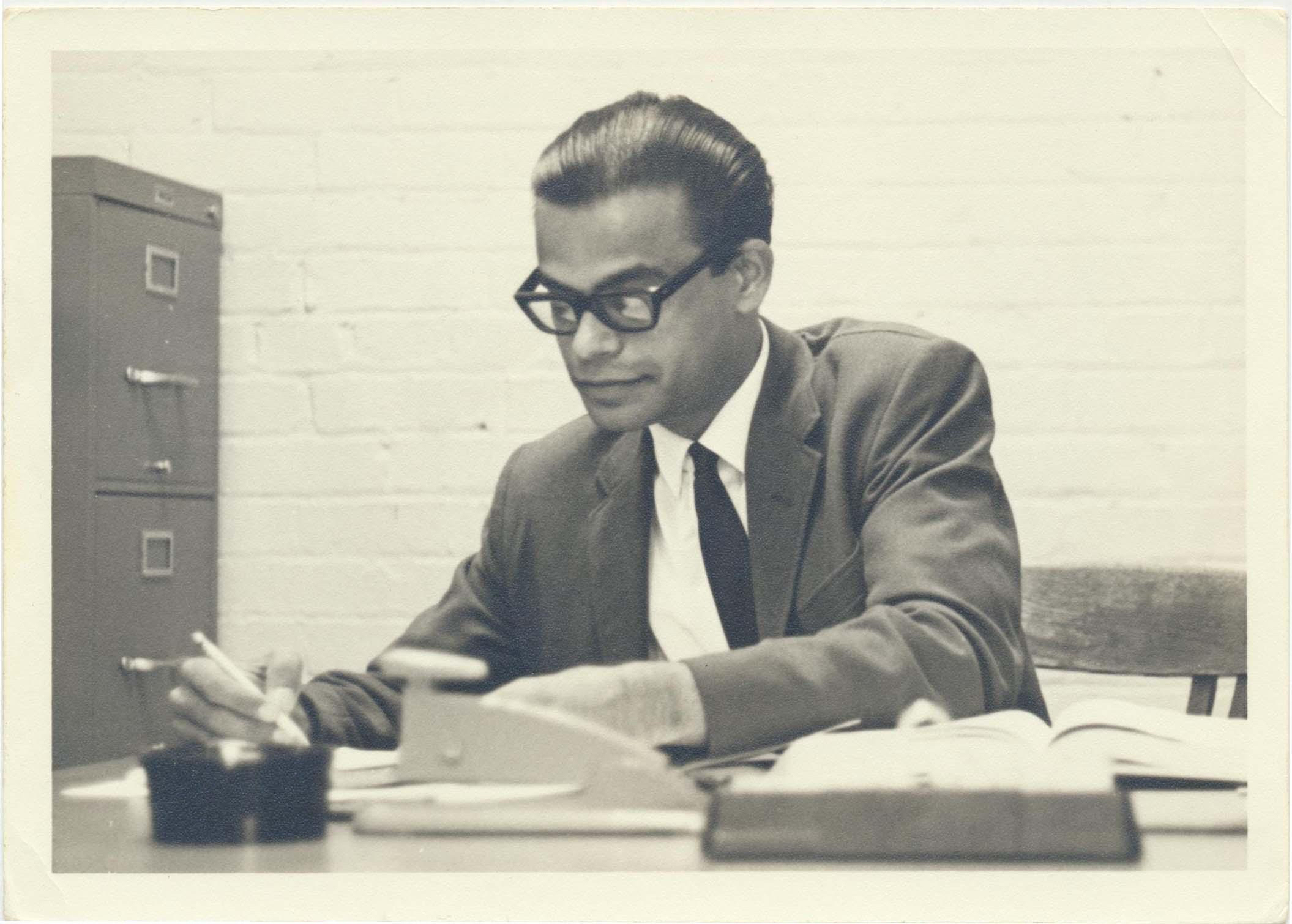

Natwar Gandhi was Chief Financial Officer of Washington, DC during 2000-2013

http://www.indiaabroad-digital.com/indiaabroad/20170825?pg=30#pg30

![]()