The Hindutva storm-troopers would feel let down, having been trained to abuse the secular Hindus, liberals, intellectuals, dissenting writers and a minority community.

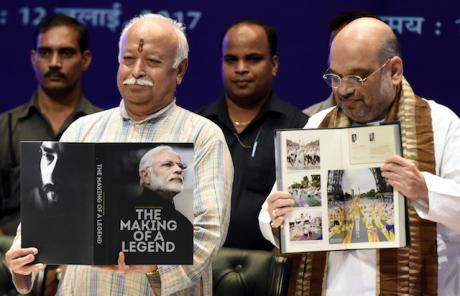

RSS Chief Mohan Bhagwat (left) and BJP National Chief Amit Shah release coffee table book on the life of the PM Narendra Modi, July 2017. Hindustan Times/Press Association. All rights reserved.

The RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh), India’s self-styled “cultural” organisation, whose political wing BJP runs the Government, held a public outreach programme designed to soften its image and make itself palatable to the opponents of its Hindu nationalism and sectarianism. That caused a political stir because as an insider says, this militant Hindu right-wing organisation, manned by a huge network of paramilitary volunteers, never admits there is anything flawed or outdated in its ideology.

The RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat has made some startling statements going against core principles of this organisation founded in 1925 with the objective of providing character training through Hindu discipline and unifying the majority Hindu community, to lead to the formation of a Hindu nation. Bhagwat’s intervention has confused followers accustomed to hard talk.

Hard talk

Bhagwat has suggested, for example, that the organisation wholeheartedly take on board the Indian Constitution. His statement endorsing the Indian Constitution – which he called “the consensus of the country” – made news, because RSS leaders have always criticised the secular and socialist Constitution of India. Commentators have predicted that if the BJP wins a clear majority in the 2019 elections, it will delete the word “secular” from the Constitution. But Bhagwat’s remarks should end the speculation that a BJP Government would amend the Constitution to turn India into a theocratic state, Hindu Rashtra.

Another key statement by Bhagwat has suggested that a Hindu nation will have space for Muslims. “The day it is said that Muslims are unwanted here, the concept of Hindutva will cease to exist”. This somewhat reassuring gesture towards Muslims comes at a time when the community is feeling besieged. It has been politically marginalised by the BJP. Not a week passes without newspaper reports of lumpen mobs carrying the Hindutva banner and threatening Muslims for selling beef or being friendly with Hindu women. In many cases, police in BJP-ruled states have shown religious bias. So, Bhagwat’s nuanced statement was very sensible and timely.

But what is going on? These statements made ahead of the general election reflect the realisation that aggressive Hindutva politics may not yield a rich harvest of votes this time around – there are limits to religious polarisation promoting the interests of the political wing of the RSS.

These statements made ahead of the general election reflect the realisation that… there are limits to religious polarisation.

Of course, Bhagwat’s lecture was promptly hailed by its member who is currently deputed to the ruling party BJP as its national general secretary. He wrote: “Bhagwat has disarmed most critics through his Glasnost.” He projected Bhagwat as a “reformer”, comparing him to Gorbachev who had said: “If not me, who? And if not now, when?”

Some ordinary Hindus and Muslims dismissed Bhagwat’s remarks as an election-eve gimmick. If an atheist starts swearing in the name of God, it will make the news. So, Bhagwat got massive publicity. Most commentators said Bhagwat must walk the talk and make the rank and file follow him.

As elections approach, political parties modify their ideological commitments, depending on the prevailing national mood as recorded by their strategists. With parliamentary elections coming up in a few months, India is sinking under a flood of political rhetoric. It is in this context that the nominated supreme leader of the RSS thought of rebranding the “cultural” organisation that runs India by remote-control.

Survival instinct

The RSS has always possessed extraordinary political instincts. Without political acumen, this cultural organisation would not have survived for more than 90 years during which it compromised with the British and kept its distance from the Congress-led freedom movement. After independence, the RSS got blamed because one of its former members killed Mahatma Gandhi. It faced a ban that was lifted after it gave an undertaking to remain a cultural organisation. Sardar Patel was then Home Minister.

While the RSS became a pariah in the eyes of most Indians because of its sectarian agenda, it was admired even by its opponents for its record of rescue and relief operations during calamities. The RSS is justifiably proud of its capacity to respond quickly through its efficient organisation. It claimed that it can deploy its volunteers even faster than the army deploys its soldiers!

The RSS found easy acceptance among a large section of Indians settled abroad. The Hollywood Hindus of America, feeling insecure about their identity, find comfort in lending digital support to RSS ideology. They would run miles from the White nationalists in their country but support the Hindu nationalists in India! A London-based Gujarati trader grumbling about India teeming with Muslims fell silent when told that white skinheads would complain that London had got far too many Patels.

The RSS tradition of public service and hard work in the areas of education and health, designed to counter the influence of missionaries among the tribals and the unprivileged Hindus, kept the organisation in good shape, even in an adverse political environment. All those years before it tasted the fruits of political power, the RSS kept working without fanfare, without publicity, quietly and secretively, attracting more volunteers to its sectarian ideology and expanding its network.

As part of its growth strategy, it says Hinduism is in danger and Hindus face a demographic challenge. Its political instinct reflects the way Hindu society has survived the threats posed by invaders, at times compromising with alien rulers but always sticking to its faith in private. All other Hindu organisations such as the Hindu Mela, Ram Rajya Parishad and Hindu Mahasabha withered away. The RSS saw ups and downs and its political wing grabbed every opportunity to mainstream itself by joining and quitting coalitions.

Their biggest opportunity came when Jayaprakash Narayan needed volunteers to fight the Indira Gandhi Government. The RSS and its political wing were more than willing to join his movement, notwithstanding ideological differences. Subsequently the socialist leader regretted the entry of the communal forces into his movement, but by then the communal outfit had gained a measure of respectability because of its association with others. The RSS and BJP have spent the past four years trying to mainstream Hindutva ideology, based on exclusion and extremism.

For this “cultural” organisation, Indian culture means pre-Islamic Indian culture.

For this “cultural” organisation, Indian culture means pre-Islamic Indian culture. It does not accept regional diversity or the differences marking different phases of India’s history. Its storm-troopers would malign any historian admiring an Indian culture that had assimilated influences from the Greek world and from Central Asia, from the Christian Jewish Near East or from Islam and from Europe. Its leaders participated in the demolition of the Babri mosque and its volunteers are ever ready to demand the renaming of the roads named after the Mogul emperors.

Under the saffron flag

Ironically, the RSS shows European influence in the garb of its volunteers, in its commitment to the model of the nation-state and its admiration for powerful European leaders who crushed the minorities!

It marches on with the saffron flag, playing temple politics and ignoring the basic tenets of the Hindu faith. Its followers cannot be called Hindu fundamentalists because, as scholar Richard Gombrich said, they do not follow the fundamentals of the Hindu faith. Some of the principles propounded by the RSS do not reflect Vedic culture, and are imports both from Islam and Christianity, who have only one central authority and one single holy book. The Hindutva warriors, who threaten dissenters and writers of books on Hinduism, were never exposed to the Vedic hymn questioning the Creator!

Respected religious leaders and learned scholars usually keep mum when politicians hijack a religion, be it Islam, Christianity, Buddhism or Hinduism. Had it not been so, the vast Hindu masses might have come to understand the sharp difference between their faith and the “Hindutva” being propagated by the RSS and its affiliated organisations.

The groups carrying saffron flags are always out to “defend” Hindu Gods and Goddesses who are supposed to protect mortals! In this version of the ancient faith, killing a cow is a sin, but killing a human acceptable.

In this version of the ancient faith, killing a cow is a sin, but killing a human acceptable.

The RSS expects its makeover to dissuade those disturbed by Hindutva extremism from deserting its political wing, whose popularity shows some signs of decline. The RSS chief decided to project a slightly liberal face at a time when Prime Minister Narendra Modi, a former RSS functionary, has run into a political storm.

There are signs of the revival of temple politics that once yielded a rich harvest of votes for the BJP. Considering the outbreak of religiosity in the political arena in the past four years, the fear of secular forces seems justified. In the coming elections, will the ruling party make even greater use of the Hindutva card since its development plans have not delivered?

Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh said the other day that the primary duty of the judiciary is to protect the secular spirit of the Constitution – a task that has become more demanding because “political disputes and electoral battles are increasingly getting laced with religious overtones, symbols, myths and prejudices”.

Modi came to power by appealing to the votaries of Hindutva as well as promising rapid economic development. The votaries called him Hindu Hridhay Samrat (Emperor of the Hindu Hearts). The promised economic nirvana attracted those opposed to religious polarisation, hate speech and political marginalisation of a significant community.

The combination of Hindutva and economic development has not worked. So, has the RSS concluded that the Hindutva card may not give a majority to the BJP? It had chosen Modi as the BJP’s nominee for the prime-ministership. It may have a Plan B in case its political wing does not get an absolute majority.

The BJP will need coalition partners and since Modi has turned out to be a polarising figure, the potential partners will need an excuse to support a party tainted with religious hatred. In that event, the RSS will quickly field Modi’s replacement from within its ranks to attract coalition partners.

The controversial but firm ties between the RSS and its political wing once led to the fall of the coalition Janata Government on the issue of “dual membership” as the RSS members in the Government refused to ditch their mentor-organisation. Now that Modi’s charisma, notwithstanding his fiery oratory, has started to diminish, Bhagwat has also made a very subtle attempt in his speech to distance the RSS from its political wing.

Now that Modi’s charisma, notwithstanding his fiery oratory, has started to diminish, Bhagwat has also made a very subtle attempt in his speech to distance the RSS from its political wing.

While the BJP leaders have gone after the Congress and its leaders past and present hammer and tongs, Bhagwat unexpectedly lauded the role of the Congress. He said the RSS did not believe in cleansing the nation of the Congress, contradicting the BJP leaders who say they would eradicate the Congress from the soil of India. Some say the RSS is preparing for the time when a hostile party comes to power again! So, Bhagwat found it necessary to make some conciliatory noises and slightly distance the RSS from its political wing.

Hour of glory

Bhagwat’s sudden appearance as a “reformer” surprised both insiders and outsiders. No questions have ever been raised within the organisation about the fundamental principles on which it was founded. This need to reform has surfaced in the organisation’s hour of glory when its political wing, for the first time in its history, commands unrestricted political power.

Since the coming of Prime Minister Modi, the RSS has gained immense influence, leading to the expansion of its nationwide network of volunteers who hold regular drills, armed with sticks. A few bureaucrats, judges, policemen and even the Army chief at times say things that please the RSS but would have horrified any past political establishment.

A mini-cultural revolution involving cultural assassinations of selected national heroes has been sweeping the nation.

A mini-cultural revolution involving cultural assassinations of selected national heroes has been sweeping the nation. All kinds of autonomous institutions are now led by RSS persons. A massive anti-Nehru campaign has been unleashed. The profile of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library has been modified. Bhagwat’s address on the RSS annual day was telecast live by the nation’s public broadcaster. Bhagwat’s public outreach programme was launched in the most prestigious government auditorium. So, in things big and small, the RSS has been richly rewarded by the Modi Government.

The RSS, for its part, let the Modi Government go against some of the principles as well as economic policies that were dear to it. Far from uniting Hindus, Modi’s divisive politics has splintered the community further. Some Hindus now feel ashamed to belong to this faith. The global brand of Hinduism has been damaged. The comparison is not appropriate, but some refer to the Muslim Brotherhood while talking of the RSS.

The outbreak of regional and sub-regional pride is not what RSS considers desirable in view of its commitment to Akhand Bharat (the one nation concept that at one time included the separated Pakistan). But regional and sub-regional pride was fuelled by the BJP leaders to win votes. If BJP-ruled Gujarat will reserve jobs for Gujaratis, the concept of one India does not go far.

Similarly, some of the Modi Government’s economic policies are what the organisations belonging to the Sangh family fought against when their party was not in power. These include the opening up of the big retail trade, privatisation, role of the foreign corporates, labour reforms and the diminished importance of self-reliance. The RSS has overlooked all this. It has silently watched Modi’s glorification as an individual at the cost of an institution which again is not part of the RSS ethos.

However, RSS has not regretted that it picked up Modi as the prime-ministerial candidate because it is Modi’s poll campaign that secured an absolute majority for the political wing of the RSS. The RSS came into the limelight and became attractive to the fence-sitters and many of its former opponents. Its influence increased, and its network expanded as new people flocked to it.

Double-edged sword

Ironically, this success has turned out to be a double-edged sword. Seen as running the Government through remote-control, the RSS has got itself exposed as an unconstitutional authority. It has come under fierce attacks from opponents of the BJP. It used to attract less hostility when the BJP was not in power.

RSS Chief Mohan Bhagwat with former PM Manmohan Singh, and BJP Leader M.M. Joshi during a cremation ceremony, August 2018. Hindustan Times/Press Association. All rights reserved.

Now its non-participation in the freedom movement or its preference for a saffron flag is recalled ever more frequently. The critics point out that its constant talk of Hindu nationalism never helped in the nation-building undertaken by the Congress leaders. The RSS showed no respect for either the national flag or such key principles of the Constitution as secularism, socialism, federalism or even democracy. Its organisational set-up is itself undemocratic.

In the name of nationalism, the RSS opposed every friendly gesture towards Pakistan. It called positive discrimination, ‘appeasement of the minorities’. Some commentators call this organisation anti-national because of this conduct and its record of exacerbating Hindu-Muslim tensions.

Its ideology is blamed for physical and verbal attacks on the minorities, the BJP leaders’ hate speeches and an aggressive campaign aided by ministers to rid some educational institutions of leftist influence. It is blamed for attacks on the critics of Hindutva and those challenging the dominant castes. Even for the Government’s failures, the RSS gets blamed by association!

Liberal critics have pointed out that Bhagwat skipped some controversial views expressed frequently by BJP leaders and followers. For example, he kept silent on the inter-religious marriages that have led to mob violence and even police harassment of Hindu girls marrying Muslims. Groups trespass into the homes of such couples or accost couples sitting in public places, questioning their identity. He did not say a word about the campaign asking the Muslims to reconvert to Hinduism, the faith of their forefathers.

In an organisation like the RSS, one cannot stray too far from the given line even in the name of reform. Bhagwat would have faced less problems in making a slight departure before its political wing polarised the nation on religious lines and exploited the fault lines of communal and caste rivalries. Many Hindus now feel charged with communal passion and support Modi precisely for his ability to “fix” the enemies of Hinduism.

In an organisation like the RSS, one cannot stray too far from the given line even in the name of reform.

Hyper-extremism

Hyper-extremism follows extremism. A mildly aggressive organisation that fuels violence is either taken over by a more violent leader or superseded by a fierier rival organisation. What a Modi does, a Yogi can do better! Had Yogi, the Hindu monk-politician, not been accommodated as a state chief minister, he could have troubled his party, the BJP, more than any opposition leader. If the RSS moves towards liberalism, the Hindutva storm-troopers, energised and empowered during the past four years, would feel let down. They have been trained to abuse the secular Hindus, liberals, intellectuals, dissenting writers and a minority community.

Organisations displaying their Hindutva credential have proliferated during the past four years and new names keep cropping up in news reports about mob violence, intimidation and lynching.

The volunteers of the vast moral police are provoked by those selling beef, entering into inter-religious marriages, or not showing respect to a Hindu God or the national flag. Women who wear short skirts or enjoy drinks in a bar have to be a bit more careful about their personal security. Romantic couples find that neither public gardens nor private homes are quite safe. The recent cases of violence will perhaps bring down the number of inter-religious marriages!

Lynching

Scholar Christopher Jaffrelot, who has written extensively on the RSS, has this to say: “Not only has the Prime Minister abstained from condemning lynchings, some legislators and ministers have extended their blessings to the lynchers. Whenever lynchers have been arrested, the local judiciary has released them on bail. If the executive, legislature and judiciary do not effectively oppose lynchings, India may remain a rule-of law country on paper and, in practice, a de facto ethno-state.”

When the ruling party president Amit Shah called Muslim infiltrators “termites”, a foreign journalist was reminded of a particular tribe in a distant land being called “cockroaches” for justifying violence against it. These days more abuses are heard in India’s political discourse than in a den of criminals. Fired by bigotry, millions have taken to social media. A large section, comfortable only in their mother tongue, convey their violent messages in Hindi written in the Roman script.

Fired by bigotry, millions have taken to social media.

In this kind of a toxic atmosphere, even the supreme leader of the cadre-based RSS, will find limits to his authority. His nuanced comments, designed for image makeover, are unlikely to lift the threat of Hindutva extremism that now comes from the expanding number of outfits that keep cropping up.

The BJP is already facing protests from its upper-caste supporters angered by a legal provision to protect the Dalits that the Modi Government was forced to enact by its coalition partners belonging to the oppressed communities. The core supporters of the RSS and its political wing have always come from the upper castes who are unhappy with what they see as “appeasement” of the Dalits!

Some Hindu leaders will denounce any reformist Hindu extremist as “a fake Hindu”. They have learnt that it pays in politics to call your secular Hindu opponent a Muslim, “sickular”, and an agent of Pakistan! Some Hindutva hotheads are asking why the Government has not passed a law to build the promised Ram Temple on the site of the demolished Babri mosque!

They can snatch back the crown they had placed on the head of the Emperor of the Hindu Hearts! The communal virus has made violent eruptions routine. It will not be easy to push this genie back into the bottle!

30 September 2018

https://www.opendemocracy.net/openindia/l-k-sharma/hyper-extremism-tends-to-follow-extremism

![]()