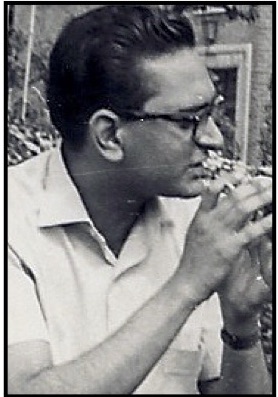

Nazmi was born in Kisumu, Kenya on March 31, 1942 and died in an accident in Nairobi on July 1, 1990. He was the 3rd child of Gulamhussein and Shirin Durrani both of whom were born in Nairobi. Nazmi’s grandfather, Alibhai Ramji, (on his father’s side) was born in Jam Timby, Naunagar State, India in 1890 and later married Avalbai. He came to Kenya when he was about 10 years old. Alibhai’s father, Ramji Kanji, had sent Alibhai (and later his younger brother) to Kenya following drought and impoverishment due to British oppression of Indian peasants.

Nazmi was born in Kisumu, Kenya on March 31, 1942 and died in an accident in Nairobi on July 1, 1990. He was the 3rd child of Gulamhussein and Shirin Durrani both of whom were born in Nairobi. Nazmi’s grandfather, Alibhai Ramji, (on his father’s side) was born in Jam Timby, Naunagar State, India in 1890 and later married Avalbai. He came to Kenya when he was about 10 years old. Alibhai’s father, Ramji Kanji, had sent Alibhai (and later his younger brother) to Kenya following drought and impoverishment due to British oppression of Indian peasants.

Nazmi studied at the Aga Khan Secondary School and Allidina Visram High School in Mombasa prior to graduating in 1965 at the University of Leicester in England. Following a Post Graduate Diploma in Education at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda in 1966, Nazmi taught at the Aga Khan High School in Mombasa before moving to Nairobi where he worked at the Library of Congress Office from 1969 until his death on July 1, 1990

In that brief working period of 24 years, Nazmi developed many interests. The selection of his writing in this book provides a glimpse into the range of his interests and work. However, it misses out the main motive that powered his writing and the vast range of his activities. While Nazmi was a left-leaning progressive intellectual, he did not come to his own until he became a member of the underground political organisation, The December Twelve Movement, towards the end of 1970s. Joining the anti-imperialist organisation helped him to make the transition from a left-leaning intellectual to a political activist who directed his energy to working for a just and more equal Kenya. This struggle motivated him until his untimely and tragic death.

As a librarian, Nazmi was aware of the central role that relevant information could play in the struggle to liberate the minds of working people from a mindset moulded by imperialism. As a teacher, he was keen to ensure that the learning and experience he had were passed on to others, particularly the younger generation growing up under neo-colonialism. As a member of the December Twelve Movement, he was active in strengthening the organisational structures which could provide a powerful force to dislodge the imperialist-imposed culture and politics in Kenya. One of the causes in which Nazmi became active was the environmental movement which embraced causes that served the needs of working people, such as campaigns to develop bicycle lanes in Nairobi so that workers could have a safe and viable means of transport to/from work.

In addition, Nazmi also became involved in cultural activities as an arm of the liberation struggle in which Nazmi was active. Along with other activists, he was against the imposition of English as the only viable language in Kenya. He thus learned Kiswahili and wrote stories, poems and historical pieces in Kiswahili so as to reach workers who used this medium of communication. Some of his poems in Kiswahili are reproduced in this book, but a more substantial collection of his resistance poetry in Kiswahili will be published under the title Tunakataa in 2017. At the same time, he supported the use of the languages of Kenyan nationalities. In this context, he sharpened his skills in his own mother tongue, Gujarati, and wrote historical and cultural articles that would increase awareness among Gujarati-speaking people. Some of his articles written and published in Gujarati are reproduced in this book. He also wrote a play in Gujarati, Katokati no Samai and translated it into English under the title An Encounter in Eastleigh. To date, the English version remains to be published. He devised also some crosswords in Gujarati for Alakmalak magazine. He wrote stories, puzzles and other learning material for children – some published in Alakmalak, others given to younger members of his own family.

Many of his activities, particularly political ones, remain to be documented. One such activity was the the use of his house in the Ngara area of Nairobi as a safe house for political work of the December Twelve Movement and the setting up of the liberation library there. The “secrete basement in a house”, mentioned below was Nazmi’s, as recorded by Durrani, S. :

Another way in which the Library Cell met the needs of the people was writing, printing and distributing underground pamphlets. Thus a number of underground pamphlets were cyclostyled by Cell members using a secret basement in a house in the [Ngara] area of Nairobi. The house itself had been a “safe” underground facility for a number of political activities, including a venue for safe meetings. It also housed the Movement’s library which served as a central reference centre for the movement. The “Notes accompanying donation of books to Cuba” (Durrani, 2008) in 2000, provide further details on the library:

Thus the liberation forces of necessity had to set up their own underground liberation libraries. Perhaps the largest one was the one run by Nazmi Durrani which provided a major reference point for December Twelve Movement which published its own newspaper Pambana (“Struggle”) in early 1980s. The library contained material which was banned in Kenya and which could lead to indefinite detention if found out. This included works of Marx, Lenin, Stalin, Castro, as well as publications from USSR and the Foreign Language Press in Beijing. This library also provided the source material for important document in the fight against the neo-colonial Moi regime such as Mwakenya’s Register of Resistance (1987), and Umoja(1989) .

In Progressive Librarianship,Durrani, S. provides some background to Nazmi’s articles in this book:

Library Cell members were active in other areas as well. One method they used was the use of open publishing avenues to create a new awareness of the history of resistance. An important contribution was that of Nazmi Durrani writing as Nazmi Ramji for security reasons. He worked as a librarian at the Library of Congress in Nairobi, but developed December Twelve Movement’s (DTM) library in a secret location. As a member of the Library Cell, he participated in all its information activities, as well as in all DTM political work. He also acted as Kanoru in Ngugi wa Thiongo’s play Maitu Njugira (Translated as “Mother Sing for me”, 1981) which was banned by the Kenya Government who then detained the author… He [Nazmi] was also responsible for compiling a number of publications circulating underground. These included Article 5 – Human Rights Violations [in Kenya] and Upande Mwingine – collections of resistance activities by workers, peasants, students and others.

He also wrote and published a series of articles in Gujarati under the heading “Biographies of patriotic Asian Kenyans” which sought to counter the Government propaganda which painted South Asian communities in a very negative light. The series was written in Gujarati and published in the Gujarati magazine, Alakmalak.

At a personal level, Nazmi remained down-to-earth and perfectly at home with all – children, youth, older people. Teresa Ongaro captures Nazmi’s personality:

If Nazmi Durrani thought his grey hair would earn him some reverence on this trip, he must have been very disappointed—to us he was just one of the guys! His sense of humour, his modesty and his generosity (one cold night in Francistown, Nazmi let someone sleep in his sleeping bag who hadn't even asked!) made him a favourite among us all. To Nazmi, solitude is for sleeping—two minutes on his own and he’d be dreaming away to glory. This trancelike state soon came to be known as Nazmititis. His endless wit provided us a regular source of comedy. However, Nazmi’s leadership qualities are doubtful—his suggestion of a venue for a meal led to the near decimation of our group's male species.

In one of his poems, Nazmi asks:

When shall we liberate

Ourselves from this mental slavery?

The struggle to liberate people’s minds from the imperialist mental slavery become Nazmi’s lifelong pursuit.

London, June 07, 2016

![]()

આ સામિયકમાં નઝમી રામજી નામના એક અભ્યાસુ લેખકની કલમે કટાર આવતી. વિક્ટોરિયા સરોવર કાંઠે આવેલા કિસુમુ ખાતે 31 માર્ચ 1942ના રોજ જન્મેલા આપણા આ નઝમુદ્દીન દૂરાણીનું એક અકસ્માતમાં નાઇરોબીમાં 01 જુલાઈ 1990ના દિવસે કારમું અવસાન થયેલું. નઝમીભાઈએ ગુજરાતી, કિસ્વાહિલી અને અંગ્રેજીમાં ય લખાણ કર્યાં છે. ખોજા પરિવારના આ નબીરાનું અવસાન થયા પછી, ગુજરાતી આલમે આ ઇતિહાસ ખોયો હોય, તેમ હાલ અનુભવાય છે.

આ સામિયકમાં નઝમી રામજી નામના એક અભ્યાસુ લેખકની કલમે કટાર આવતી. વિક્ટોરિયા સરોવર કાંઠે આવેલા કિસુમુ ખાતે 31 માર્ચ 1942ના રોજ જન્મેલા આપણા આ નઝમુદ્દીન દૂરાણીનું એક અકસ્માતમાં નાઇરોબીમાં 01 જુલાઈ 1990ના દિવસે કારમું અવસાન થયેલું. નઝમીભાઈએ ગુજરાતી, કિસ્વાહિલી અને અંગ્રેજીમાં ય લખાણ કર્યાં છે. ખોજા પરિવારના આ નબીરાનું અવસાન થયા પછી, ગુજરાતી આલમે આ ઇતિહાસ ખોયો હોય, તેમ હાલ અનુભવાય છે.