He disliked statues of himself, yet they exist everywhere

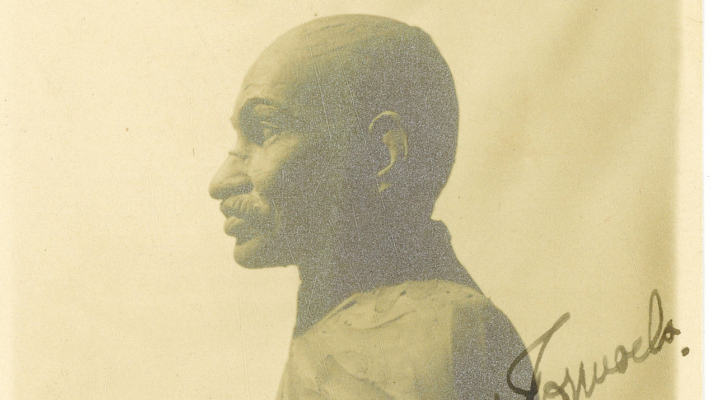

Nancy Cox-McCormack, sculpted M.K. Gandhi while he went about his work while attending the Second Round Table Conference. She presented his son, Devadas Gandhi, (who was present there) a small photograph of her work in progress, with “unfinished” written across it

Image provided by Gopalkrishna Gandhi

Gandhi has gone wholly, energetically unheeded in one matter. Learning that a Gandhi statue was proposed to be put up on the grounds of an ensuing session of the Congress, he wrote in Harijan on February 11, 1939: “It will be a waste of good money to spend Rs 25,000 on erecting a clay or metallic statue of the figure of man who is himself made of clay…” He went on to say he disliked the very idea of statues and images of him being put up.

But he was to relent and let at least four sculptors work on their clay models, ‘live’.

Eight years before his 1939 statement Gandhi permitted two American sculptors, Jo Davidson (1883-1952) and Nancy Cox-McCormack (1885-1967), to sculpt him while he went about his work. This was in the October of 1931, in London, when he was attending the Second Round Table Conference. These two and the British sculptor, Clare Sheridan (1885-1970, a cousin of Churchill, admirer of Lenin and, briefly, a lover of Charlie Chaplin), had importuned him to let them sculpt him, ‘undisturbed’. Davidson bantered as he carved the clay. “I see,” quipped Gandhi, “you make heroes out of mud.” Davidson responded, “And sometimes vice versa.” Cox-McCormack worked rather more silently, giving Gandhi’s son, Devadas (who was present), a small photograph of her work in progress, with “unfinished” written across it. Clare Sheridan, who observed Gandhi not just in the setting but even beyond, records: “I was present at a reception at the Carlton Hotel in honour of the Round Table delegates. There were innumerable politicians, several ex-Viceroys and a galaxy of Maharajahs. Gandhi did not want to seem unfriendly by abstaining, but worldly parties were not in his line. As a friendly gesture however, he put in an appearance, that is to say he ventured as far as the doorway, and there he stood enframed and hesitating. Almost immediately there was a general movement of the crowd towards him. The Maharajah of Bikaner, magnificently tall and imposing, was one of the first who went forward to greet him. Lady Minto, widow of a Viceroy and an old friend of my family’s, said to me: ‘I must know him — you must introduce me —’ and the two remained for some time absorbed in conversation.”

To Clara Quien (1903-1987), a sculptor of Dutch extraction, also belongs the distinction of having sculpted Gandhi ‘live’. Quien was a student of the Florentine master, Andreotti. With her husband, she travelled through Russia and China during World War I and lived for a significant period in the 1940s in the Kashmir Valley. Travelling in India, Quien got the opportunity to meet and sculpt Gandhi, in Sevagram.

Two non-sculpting artists, the British wood-engraver, Clara Leighton (1898-1989), and the expressionist draughtsman, Feliks Topolski (1907-1989), were also to work on him from life, on their charcoal and pencil drawings.

The sculpting interest has outlived Gandhi.

Fredda Brilliant (1903-1999), a Polish sculptor of “gypsy creativity”, was an ardent socialist. She has sculpted Thomas Mann, Georgi Dimitrov, Chekhov, Mayakovsky and John F. Kennedy among others. Her best-known work is, however, of a furrowed, introspecting Gandhi seated bare-chested and cross-legged, knees jutting out of the pedestal, at the centre of Tavistock Square, London. Brilliant did not see Gandhi but pored over many photographs of him with her sharp and highly critical eyes, which led to the making, by her sharp, sensitive hands, of her Gandhi.

Gandhi never visited China or Japan and one would imagine he had little impact on artists there. Not so. Beijing has an unusual Gandhi statue by Yuan Xikun, showing him reading a book that is held up by him. He looks like he could be a friend of one of the three Chinese poets Vikram Seth has translated. Gandhi is reading the book with care and — worry. What is the book? One will never know but if Yuan’s passion for the physical environment is anything to go by, the book is one that was unwritten in Gandhi’s time — Martin Rees’s deeply troubling work on the future of humankind — Our Final Century.

Likewise, there is an ineffably gentle statue of the Mahatma in Tokyo’s leafy Tetsugakudo Park in Nakano-ku. He is very Japanese-looking in that, very Zen, a survivor of Hiroshima. His palms are joined in a namaste that challenges the world of violence to rescue itself from itself. Nándor Wagner, a sculptor of Hungarian descent, had long made Japan his home and created a garden of philosophy with eight figures, including the Buddha, Jesus, Lao Tse, and — Gandhi.

Gandhi had a deeply fulfilling, formative association with Tolstoy, conducted wholly through correspondence, after his transformative reading of Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God is Within You. But that apart, one would not imagine Gandhi having a ‘presence’ in Russia’s imagination. And yet, the sculptor, Dmitry Ryabichev, and his son, Aleksander Ryabichev, have been inspired to do a most extraordinary statue of Gandhi, seated, arm upraised in a posture that is as indefinable as it is unforgettable. It reminds one at once of Rodin’s The Thinker. The original is in Delhi’s Rajghat complex, an edition in Moscow, in the garden of the Indian ambassador’s residence.

South African Tinka Christopher’s young, wind-blown advocate Gandhi in Johannesburg stands, literally, on a stunning footing of its own. V.P. Karmarkar’s bronze statue of Gandhi in Nairobi, unveiled by the then vice-president of India, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, in 1956, has been historically and artistically compelling.

Latin America and Gandhi have an ideational connect that defies empirical explaining. There are, in Brazil alone, three Gandhi statues: one in the Ibirapuera park in São Paulo, another statue by Gautam Pal in the city of Londrina (Province of Paraná) and the third in Cinelandia in downtown Rio de Janeiro by the veteran Sankho Chaudhuri. But there it is, personifying the inspiration that Gandhi was for Adolfo Pérez Esquivel. The doughty Argentinian sculptor and peace activist has made a bronze statue of Gandhi that stands in Barcelona with his joined palms glistening — a sculpting coup. Barcelona, incidentally, is a portrait sculptors’ paradise boasting of statues, among others, of Anne Frank, George Orwell and John Lennon.

The latest Gandhi statue outside India is that by the Scottish sculptor, Philip Jackson (born 1944), standing in the company of Lincoln, Smuts, Churchill and Mandela, in Parliament Square, London. Jackson’s work captures the strong silence, the extraordinarily powerful simplicity of the subject. And it exemplifies Jackson’s description of his art as “grow(ing) out of the ground, the texture resembles tree bark, rock, or lava flow”.

The most overarching statue of Gandhi, anywhere, has to be Debi Prasad Roy Chowdhury’s majestic bronze. That strident Gandhi is to be seen in editions of it beyond its original location in New Delhi. Ram Sutar’s meditative one, also in bronze, awes those who see it. Replicas of it have been sent across the world from India.

Gandhi statues in India and elsewhere have been subject to vandalism. Like those of the other greatly sculpted figure, B.R. Ambedkar, Gandhi statues have been disfigured and messed up by assailants, mainly from the Right. The radical Left has not spared them either. This is no surprise, given that he thought and lived challengingly.

But there is another sculpted Gandhi which survives, even thrives on, vandalism. This one is in no bronze or marble. It will be found in no art catalogue, no list of Gandhi-sculptures. It will not be considered ‘art’. In its frank depiction of the un-handsome looks of its subject it can have no peer. It shows him just as he was, only more un-prepossessing. It has been sculpted by what may be called the sculpting genius of our people. I refer to the ‘very ordinary’ cement-plaster bust of Gandhi that stands on dusty pedestals in the cities, towns and villages of India. This bust, for all its rusticity, says something vastly simpler but so much rarer than do the great bronzes and rock-cuts. It says, simply, ‘This man told no lies, was honest, bore no hatred towards anyone.’

This ubiquitous ‘common’ bust is, in a sense, like Cox-McCormack’s work, “unfinished”. Why so? Because Gandhi’s work among the people amid whom his bust stands is unfinished. And will so remain as long as fear rules freedom, corruption dominates governance and suspicion fans hatred between our communities.

courtesy : “The Telegraph”, 21 October 2018

![]()