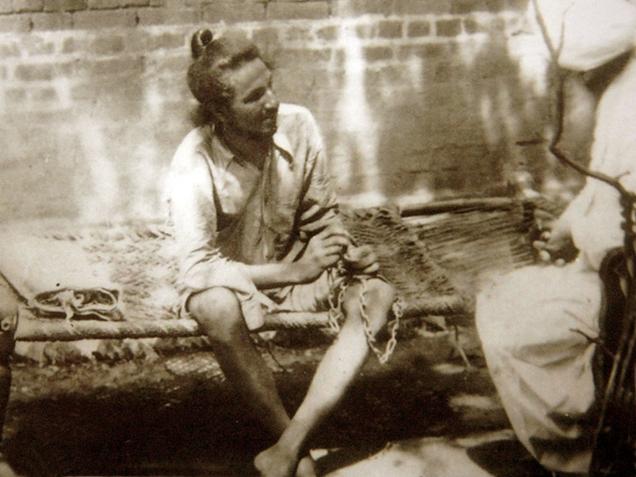

"Handcuffed and beaten, Bhagat Singh added a new dimension to his courage when he resorted to a hunger strike in prison asking the ‘Lahore prisoners’ to be treated as political prisoners, not ‘common criminals’." Photo: The Hindu Archives

On Bhagat Singh’s death anniversary, the Congress should pause and reflect on how his political thought informed its agenda. Inspiration from the 1931 Bhagat Singh-inspired Karachi Resolution could help the party understand the magnitude of its challenge today

Eighty-five years ago this day, March 23, 1931, Gandhi and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel were on a train from Delhi to Karachi. They were going to the seaport city to attend the Congress’s annual session. Every such session used to be memorable but the Karachi Congress was to be more than memorable, it was going to be momentous.

The Gandhi-Irwin accord, by which Congress was to call off “civil disobedience” in return for the release of all satyagrahi prisoners, had been reached only a few days earlier following a fortnight of intense parleying between Gandhi and the Viceroy, Lord Irwin. Satyagrahis were to be released from jail, salt was to be freed for collection in coastal areas, and forfeited lands were to be returned. And at the upcoming Round Table Conference in London, Gandhi was to speak for the Congress’s goal of Swaraj. The nation was fairly thrilled by all this because the pact had, for the first time, brought Gandhi and the Viceroy, the Congress and the Raj on a par.

As the train sped Gandhi and Patel towards Karachi, they must have been preoccupied with thoughts on the work ahead at the session where the younger Gujarati was to take over from Jawaharlal Nehru as Congress president and where Nehru was to present a draft resolution on the Congress’s major goals for Swaraj.

Gandhi was 61 at the time, Patel 55 and Nehru 41. The first two were not quite ‘old’ yet, the third was still young. But a fourth Indian, not inching towards Karachi, not a Congressman, not a satyagrahi, no Gandhian, Patelite or Nehruvian, had in the meantime burst upon the political imagination of India like a blinding meteor, dimming the sparkling asterisms of the Congress.

Date with the gallows

Bhagat Singh at 23, younger than young, brave, thoughtful, wise beyond his years, on the morning of March 23, 1931 in his cell in Lahore Jail, had been in custody for nearly a year, facing trials with fellow revolutionaries from the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association including Shivaram Rajguru and Sukhdev Thapar, for the killing of Lahore’s Assistant Superintendent of Police John Saunders on December 17, 1928 and for “waging war against the King”. This last charge came from Bhagat Singh’s throwing, with Batukeshwar Dutt, bombs and leaflets into the Central Legislative Assembly chambers in New Delhi on April 8, 1929.

Handcuffed and beaten, Bhagat Singh added a new dimension to his courage when he resorted to a hunger strike in prison asking the ‘Lahore prisoners’ to be treated as political prisoners, not ‘common criminals’. Among the voices raised to protest against the mistreatment of the Lahore heroes was that of Mohammed Ali Jinnah. Speaking in the Central Assembly on September 12, 1929, his salty, satiric voice said: “Bhagat Singh is not asking for spring mattresses or dressing tables… the man who goes on hunger strike has a soul. He is moved by that soul, and he believes in the justice of his cause. He is no ordinary criminal… guilty of cold-blooded, sordid, wicked crime.”

Once the death sentence was passed, Irwin blocked all appeals for clemency and commutation, including that from Gandhi. The same panic led to Bhagat Singh’s date with the gallows being advanced from the dawn of March 24 to the still darkness of the night of March 23. It is said Bhagat Singh walked to the scaffold, head held high, with the slogan ‘Inquilab Zindabad’ on his lips. Also, that he kissed the noose as it was lowered to his head. What is known is that empowered magistrates declined to supervise the execution and an honorary judge was asked to fill in. The three bodies were then hurriedly and secretly cremated and the ashes taken furtively in the night and lowered into the Sutlej near Ferozepur.

A defining presence in absentia

Bhagat Singh played, in the hours and days after his hanging, a role that history has not recognised, acknowledged or learnt from. Quite incredibly, Bhagat Singh’s became the most important ideational presence at the Karachi Congress, virtually dictating its agenda and defining the draft resolution which Nehru put together and Gandhi edited. Bhagat Singh was, in effect, Congress president at that session.

Gandhi said through the Karachi Congress and later that he deplored the cult of assassination and political violence. It has to be said for the ideological integrity of the Congress of the day that it began its resolution “… disassociating itself from and disapproving of political violence in any shape or form”. But it is also to the credit of the Congress’s sensitivity of the national mood that it deplored the triple executions “… as an act of wanton vengeance and a deliberate flouting of the unanimous demand of the nation for commutation”.

Of far greater significance than the Karachi Congress’s solidarity with Bhagat Singh’s person was the Congress’s bonding with Bhagat Singh’s political thought. The resolution on India’s future under a scheme of Fundamental Rights and Duties that Nehru drafted, we know from Nehru’s own notes on it, was edited by Gandhi. But it was also unmistakably influenced by Bhagat Singh. A couple of examples suffice to show this.

In a statement issued by him with Batukeshwar Dutt dated June 6, 1928, Bhagat Singh had said: “… labourers and producers, despite being part of the mainstream, are victims of exploitation and have been denied basic human rights… Farmers, who produce, die of hunger. The weaver who weaves clothes for others cannot do so for his own family and children… Masons, carpenters, ironsmiths who build huge palaces die living in huts and slums. On the other side, capitalist exploiters, anti-social elements, spend crores of rupees on their fashion and enjoyment…”

Nehru’s Karachi text began with: “This Congress is of the opinion that in order to end the exploitation of the masses, political freedom must include real economic freedom of the starving millions.” And his Resolution, as further refined by the All India Congress Committee, went on to give under paragraphs titled ‘Labour’, and ‘Taxation & Expenditure’, the goals: “… Labour to be freed from serfdom and conditions bordering on serfdom… Peasants and workers shall have the right to form unions to protect their interest… giving relief to the smaller peasantry…”

In Why I am an Atheist (October 5-6, 1930) Bhagat Singh had written: “The day shall usher in a new era of liberty when a large number of men and women, taking courage from the idea of serving humanity… will wage a war against their oppressors, tyrants or exploiters… to establish liberty and peace.” A major Karachi Congress formulation read: “Every citizen of India has the right of free expression of opinion, the right of free association and combination, and the right to assemble peacefully and without arms, for a purpose not opposed to law or morality.”

Karachi’s resolutions, it is so clear, refracted themselves into the Preamble to the Constitution of India and its chapter on Fundamental Rights. To that extent Bhagat Singh was, in his permeating influence, an in-absentia member of the Constituent Assembly’s Drafting Committee.

There can be no doubt that Bhagat Singh’s execution led to the Karachi Resolution saying under ‘Fundamental Rights’: “There shall be no capital punishment.” That was a Congress resolution, a Congress resolve. As the population in India’s death rows teems with men and women convicted not just for ‘plain murder’, but assassinations and ‘waging war against the state’, and as sedition is invoked to smother dissent in ways that would make Lord Irwin look evangelical, let the Congress give up ambiguity on capital punishment and say that those sentenced to death in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case, having spent a quarter of a century in jail for indirect involvement, should not hang. But beyond the matter of ‘to hang or not to hang’, let the Congress address the coarseness that has crept into our criminal investigation and prison systems, with the third degree, surveillance, and random arrests becoming routine. Bhagat Singh moved Nehru’s pen in Karachi. He can charge Congress’s laptops today.

The lessons from 85 years ago

As in 1931, so also in 2016, the Congress is not in power in Delhi. It has played the role of an alert opposition in some crucial ways, with fortitude and success. But being a strong opposition party is one thing, being a tribune of the people is another. The Karachi resolutions of 1931 are there, in black and white, for it to turn to for guidance, for inspiration.

The Karachi resolve, “…the State shall own or control key industries and services, mineral resources, railways, waterways, shipping, and other means of public transport”, is an orphan today. Where does the Congress stand on the disinvestment of national assets? Where does it stand on the behemoth of monopoly control over India’s mineral resources, legal and illegal?

Likewise, what does the Congress plan to do, in these self-defining times, on the Karachi resolve to give “…protection against the economic consequences of old age, sickness and unemployment”? It has been left to individuals like Prabhat Patnaik and movements like those led by Aruna Roy to fight for a universal pension in India. Cannot the Congress bestir itself on something as basic as that? Karachi has mandated it to.

“Labour to be freed from serfdom and conditions bordering on serfdom” was a Karachi resolve. Migrant labour is India’s grimmest reality. It is a fluid serfdom, a floating servitude.

Can India, on the eve of elections to several States, expect from Congress a testament as foundational to its future as a Democratic Republic as its 1931 Bhagat Singh-inspired Resolution was for the attainment of Swaraj?

(Gopalkrishna Gandhi is Distinguished Professor of History and Politics, Ashoka University.)

courtesy : http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/return-to-the-revolutionary-road/article8386162.ece?homepage=true

![]()