હાશ ! છેવટ ભારતની જનતાએ ચોખ્ખી બહુમતીથી એક પક્ષને પોતાના દેશનો વહીવટ કરવાને માટે વરમાળા પહેરાવી દીધી. હવે નિરાંત. સરકાર માઈ બાપનું ભલું થાજો. હવે એઈને સહુને રોટલો, મીઠું માત્ર નહીં પણ માથે ઘી અને ગોળનો દડબું અને ડુંગળી પણ ખાવા મળશે. વળી, બધાયને એયને મજાનું રહેવાને ઘર અને હરવા ફરવાને એક એક વાહન પણ મળી જાશે પછી શેની ચિંતા ? કહું છું, હરખ હવે તું હિન્દુસ્તાન. જો કે અત્યાર સુધીમાં કેટલીક હકીકતો વાંચવામાં અને સંભાળવામાં આવી છે એનું સ્મરણ થતાં આ હરખને ગ્રહણ લાગ્યા વિના નથી રહેતું.

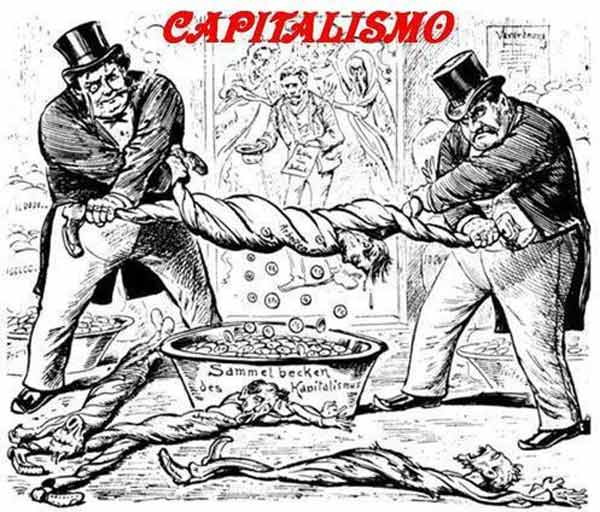

ભારત દેશમાં અંદાજે લગભગ 23 જેટલા કરોડાધિપતિઓ છે જેનો આનંદ થવો જોઈએ જેને આ હકીકત સામે મૂકી જુઓ : દેશની 25%થી પણ વધુ જનસંખ્યા ગરીબીની રેખા નીચે જીવે છે એટલે કે તમારા જ ચાર બાળકોમાંથી એક ભૂખ્યું, નાગું, ઘર વિનાનું, શિક્ષણ અને તબીબી સારવાર વિનાનું રઝળે છે. આઝાદીના સાડા છ દાયકા વીત્યા છતાં નિરક્ષરતા અને નબળું સ્વાસ્થ્ય એ મોટો પડકાર છે જેનાથી પેલા કરોડાધિપતિઓનાં સુંવાળા જીવનના તેઓ ભાગીદાર નથી બની શકતા.

વાઈબ્રન્ટ ગુજરાતના મોડેલનો ઉપયોગ હવે સમગ્ર દેશના વિકાસ માટે કરવાના આયોજનો થવા લાગ્યાં છે. પરિણામે વિદેશી કંપનીઓ લાખો-કરોડો ડોલર ખર્ચીને ભારતમાં ઉદ્યોગ-ધંધાઓ ચલાવશે અને આપણે માલેતુજાર થવાની ઝંખનામાં એ કંપનીઓમાં રોજી મેળવતા થઇ જઈશું. તો હવે આ હકીકત તપાસીએ : વિકાસ માટેની આ દિશા પકડવાને કારણે દેશી ઉદ્યોગ-ધંધાઓ પડી ભાંગશે અને કારીગરો તથા વેપારીઓ વિદેશી માલિકીના કારખાનાંઓ અને બહુ રાષ્ટ્રીય વેપારી કંપનીઓમાં વાણોતર તરીકે જિંદગી પૂરી કરશે જેમાં તેમના કાર્ય કૌશલ અને કુનેહનો ઉપયોગ ક્યાંથી થાય ? ગ્રામ્ય વિસ્તારના અને નાનાં શહેરના લોકોના રોજગારની તકો લૂંટી લઈને તેમને ‘અમે રોજગારીની નવી તકો આપીશું’ એમ કહીને શહેર ભણી જવા લલચાવે પણ છેવટ એ લોકોની તનતોડ મહેનતને કારણે ભારતના કેટલાક મેનેજર અને વિદેશી કંપનીઓના ડાયરેક્ટરના ખિસ્સાં દેશના કારીગરોના પગાર કરતાં સેંકડો ગણા પગારથી ભરાય તેનું શું ?

ભારતના ફેશન ડિઝાઈનરોનાં તૈયાર થયેલ કપડાં વિદેશમાં ખપે છે. દર વર્ષે કરોડો ડોલરની કિંમતનું કાપડ નિકાસ થાય છે. ગુચી, લુઈ વીટોં, શનેલ અને જ્યોર્જિયો આર્માની જેવા આંતરરાષ્ટ્રીય ખ્યાતિ ધરાવતા સ્ટોર્સની શાખાઓ ભારતમાં ખુલવા માંડી છે. હવે આ સિદ્ધિને સામે પલ્લે એક બીજી સત્ય હકીકત મુકીને તપાસીએ : કરોડો ડોલરનું કાપડ નિકાસ થાય છે તો ભારતના જ લાખો લોકો ચીંથરેહાલ કાં ફરે ? અત્યંત મોંઘા દાટ સ્ટોર્સમાંથી ખરીદી કરનારા લાખોપતિ કોની ક્માઈનું ખાય છે ?

ગુજરાત આધુનિક ઉદ્યોગ-ધંધાઓ જેવા કે પેટ્રોલ, સિમેન્ટ હીરા વગેરેના વધતા જતા પ્રસાર માટે માત્ર દેશમાં જ નહીં બલકે પૂરા વિશ્વમાં સુવિખ્યાત બને છે. આ ઉપલબ્ધિની સામે બીજી એક સચ્ચાઈ જોઈએ : હવે ગુજરાતે મોહન (ભગવાન શ્રી કૃષ્ણ) અને મોહન (મો.ક. ગાંધી) બનાવવાનું બંધ કરીને આતંકવાદીઓ બનાવવાનું શરુ કર્યું છે તેનું શું ?

બેંગ્લોર આઈ.ટી. અને કોલ સેન્ટર માટે જગ વિખ્યાત બન્યું છે તો એ સફળતાની સામે એક હકીકત જાણી લઈએ : કર્ણાટકના 27 જિલ્લાઓના રહેવાસીઓ એચ.આઈ.વી. એઈડ્સથી પીડાય છે. એક અંદાજ મુજબ હાલ પાંચથી દસ લાખ લોકો તેના શિકાર બન્યા છે. જો આ ભયાનક રોગ રોકવાનું કામ યુદ્ધના ધોરણે નહીં લેવામાં આવે તો આંકડો વીસથી પચીસ લાખ સુધી પહોંચી જવાની વકી છે.

હવે કેટલીક માનવ બુદ્ધિ અને સમજ શક્તિની વક્રતાઓ પણ જોઈએ. ભારતમાં અણુ શક્તિની સાથે અણુશસ્ત્રોના ઉત્પાદનમાં ઉત્તરોત્તર વધારો થાય છે. એક અણુ શસ્ત્રના વોર હેડનું ‘સ્માઈલિંગ બુદ્ધ’ એવું નામાભિધાન કર્યું. અહિંસાના પરમ ઉપાસકનું નામ હિંસાના ચરમ વિનાશક શસ્ત્ર સાથે કેવી રીતે જોડી શકાય ? એવી જ રીતે યુ.એન.નું શાંતિદળ કે જે સશસ્ત્ર સેનાનું જ બનેલ હોય છે એ કહેવાતા શાન્તિ દળમાં ભારતનું પ્રદાન બીજા નંબરનું છે; આશરે 10,000 સૈનિકોનું. શાબ્બાશ ભારત દેશના સુકાનીઓ ! કદાચ તમે વિસરી ગયા હશો કે આ ભૂમિએ ગૌતમ બુદ્ધ, મહાવીર અને ગાંધી જેવા અહિંસાના પ્રબોધકો વિશ્વને ચરણે ધર્યા છે. મુંબઈ વાણિજ્ય, વેપાર, ક્રિકેટ અને હિન્દી ફિલ્મ માટે જગ વિખ્યાત બન્યું છે. સાથે સાથે દુનિયાનું પાંચમાં નંબરનું ગીચ વસ્તી ધરાવનાર શહેર છે અને ગંદકી તથા લાંચ રૂશ્વતનું પણ થાણું છે. ઇ.સ. 2005માં ભારતમાં લગભગ 13000 નવા લખપતિ થયા હોવાનું નોંધાયું જેમાંના મોટા ભાગના મુંબઈવાસી છે અને છતાં ધારાવી જેવી વિશ્વની સહુથી મોટી ઝુંપડપટ્ટી પણ ત્યાંની જ ઉપજ છે.

ભારતના 1.25 અબજ નાગરિકો એ વાતનો જરૂર હરખ કરી શકે કે અંબાણી જેવા ઉદ્યોગપતિઓ, લીકર અને એરલાઈનના માલિકો, તાતા ઇન્ડસ્ટ્રીઝ, ઈન્ફોસીસ જેવી આઈ.ટી. કંપનીઓ, સાનિયા મિર્ઝા જેવા રમતવીરો, મીરા નાયર જેવા ફિલ્મ નિર્માતાઓ, નામાંકિત હાર્ટ સર્જનો, સુનીલ મિત્તલ જેવા ટેલીકોમના રાજા જેવાઓના નામ પશ્ચિમી ઉદ્યોગ અને વેપારી જગતને થથરાવે છે. અરે એટલે જ તો બ્રિટન અને અમેરિકા આપણા દેશના માનવ અધિકાર ક્ષેત્રે અતિ શરમજનક ઇતિહાસ સામે આંખ આડા કાન કરીને પણ વેપારી કરારો કરવા સદા તત્પર રહે છે અને હસતું મોઢું રાખીને હસ્તધૂનન કરે છે. અફસોસ માત્ર એટલો જ છે કે આદિવાસીઓ, સ્ત્રીઓ, બાળકો, લઘુમતી કોમ અને ગ્રામવાસીઓ આ વિકાસ યાત્રાનું પુણ્ય મળે તેની રાહ છેલ્લા છ દાયકાથી જુએ છે એમની ધીરજ ખૂટી લાગે છે.

આ નવી સરકારને માથે ઉપર ગણાવી તે બધી સિદ્ધિઓનો હરખ તમામ નાગરિકોને થાય એવો વહીવટ આપવાની જવાબદારી આવી પડી છે. છે કોઈની પાસે જાદુઈ છડી ?

e.mail : 71abuch@gmail.com

![]()

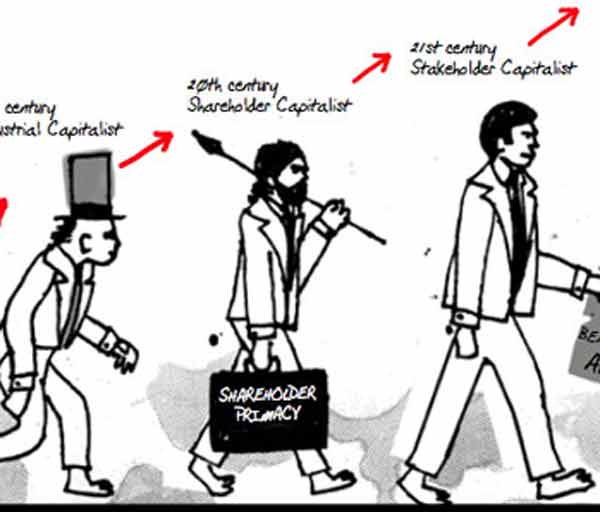

ઉદારીકરણ અને નવતર મૂડીવાદના વ્યાપક ફેલાવા પછી ખાસ કરીને એશિયાઈ રાષ્ટ્રોમાં 'ક્રોની કેપિટાલિઝમ’ (સહભાગી મૂડીવાદ) શબ્દ અને પ્રથા બહુ વ્યાપક બન્યા છે. એના વિવિધ અર્થઘટન જોવા મળે છે. ઘણાને મૂડીવાદ, નવતર મૂડીવાદ અને સહભાગી વચ્ચેનો ભેદ સમજાતો નથી. વિકાસના મુખ્ય ક્ષેત્રો જેવા કે, માળખાકીય સગવડો, વીજ ઉત્પાદન, રાષ્ટૃીય ઘોરીમાર્ગ, ખનીજ આધારિત મોટા ઉદ્યોગો તેમ જ પેટ્રોલિયમ અને પેટ્રોકેમિકલ ઉદ્યોગોમાં ખાનગીક્ષેત્રના પ્રવેશ પછી ઔદ્યોગિક વિકાસ અને સુવિધા માટે સરકાર પર આધાર રાખવો પડે છે.

ઉદારીકરણ અને નવતર મૂડીવાદના વ્યાપક ફેલાવા પછી ખાસ કરીને એશિયાઈ રાષ્ટ્રોમાં 'ક્રોની કેપિટાલિઝમ’ (સહભાગી મૂડીવાદ) શબ્દ અને પ્રથા બહુ વ્યાપક બન્યા છે. એના વિવિધ અર્થઘટન જોવા મળે છે. ઘણાને મૂડીવાદ, નવતર મૂડીવાદ અને સહભાગી વચ્ચેનો ભેદ સમજાતો નથી. વિકાસના મુખ્ય ક્ષેત્રો જેવા કે, માળખાકીય સગવડો, વીજ ઉત્પાદન, રાષ્ટૃીય ઘોરીમાર્ગ, ખનીજ આધારિત મોટા ઉદ્યોગો તેમ જ પેટ્રોલિયમ અને પેટ્રોકેમિકલ ઉદ્યોગોમાં ખાનગીક્ષેત્રના પ્રવેશ પછી ઔદ્યોગિક વિકાસ અને સુવિધા માટે સરકાર પર આધાર રાખવો પડે છે. તો ય બફેટને લાગ્યું કે એણે આવી શરૂઆત મોડી આરંભી. અખબારના ફેરિયાની કામગીરી કરતાં કરતાં કરેલી બચતમાંથી ૧૪ વરસની ઉંમરે વોરને એક નાનું ખેતર ખરીદ્યું; કારણ, વોરન જાણતા હતા કે નાની બચતમાંથી મોટા કામ શક્ય બને છે. આ વાતને વરસો વીતી ગયાં પણ વોરન આજે પણ અમેરિકાના ઓમાહા નામના નાના શહેરમાં એ જ ત્રણ બેડરૂમના મકાનમાં રહે છે. જે એણે પ૦ વરસ પહેલાં એના લગ્ન થયા ત્યારે ખરીદ્યું હતું. વોરનને એની જરૂરિયાતો આ મકાન પૂરી પાડે છે.

તો ય બફેટને લાગ્યું કે એણે આવી શરૂઆત મોડી આરંભી. અખબારના ફેરિયાની કામગીરી કરતાં કરતાં કરેલી બચતમાંથી ૧૪ વરસની ઉંમરે વોરને એક નાનું ખેતર ખરીદ્યું; કારણ, વોરન જાણતા હતા કે નાની બચતમાંથી મોટા કામ શક્ય બને છે. આ વાતને વરસો વીતી ગયાં પણ વોરન આજે પણ અમેરિકાના ઓમાહા નામના નાના શહેરમાં એ જ ત્રણ બેડરૂમના મકાનમાં રહે છે. જે એણે પ૦ વરસ પહેલાં એના લગ્ન થયા ત્યારે ખરીદ્યું હતું. વોરનને એની જરૂરિયાતો આ મકાન પૂરી પાડે છે.