As a college student she was sensitive to the issues that surrounded the society. She was instrumental in collecting donations and charity for the victims of Anamat Aandolan of 1989 in Gujarat. She had kept them in her house and would distribute with her friends to victims, only to get a threat of her house being burntif she gave it to Muslims. She was aghast.

As a college student she was sensitive to the issues that surrounded the society. She was instrumental in collecting donations and charity for the victims of Anamat Aandolan of 1989 in Gujarat. She had kept them in her house and would distribute with her friends to victims, only to get a threat of her house being burntif she gave it to Muslims. She was aghast.

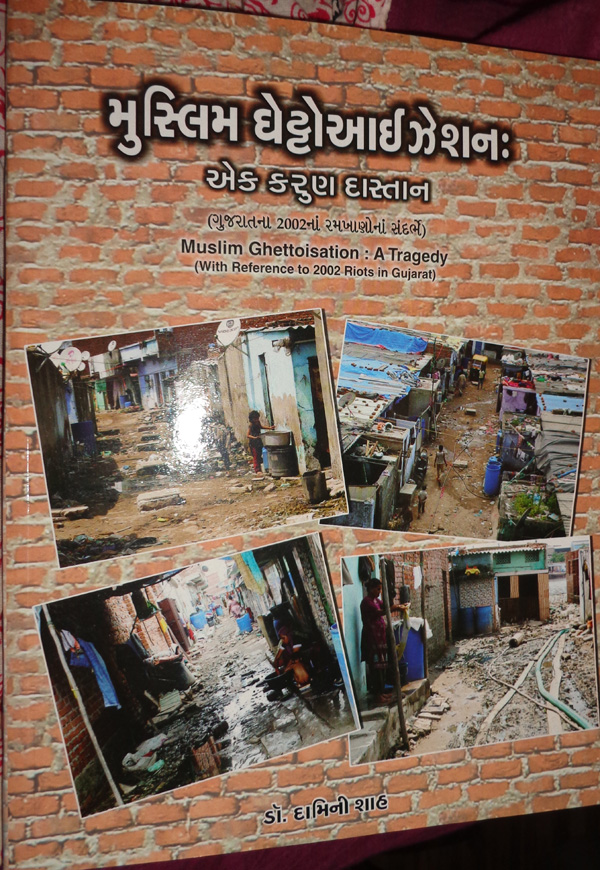

Now, After two decades, when Dr. Damini has come out with a book “Muslim Ghettoisation : A tragedy” there is that element of commitment which is fast evaporating from our society called ‘sensitivity to the issues that surround not necessarily to you but to your people, who may not belong to the community and religion you are born or live with.

Dr. Damini Shah is a lecturer at Gujarat Vidyapeeth who is a scholar and researcher for years is a simple, short statured lady with steel like determination and courage. She did what many could not do or document, many did not bother or avoided to be heard of even.

Dr. Shah has systematically analysed various aspects of living conditions and depicted the present scenario of the Muslim settlements in her 172 paged book which has been written with reference to 2002 riots in Gujarat.

In her documented research thesis, Dr Shah narrates the first account of the settlement dwellers that once many of them were once well to do, had good and clean hygienic conditions to live with and to boast of being civilised progressive Muslims. But, after riots, they said they were shocked to see their own people disowning them, not willing to see them back in their very areas where together they had passed years..and at a place which was rightfully owned by the, Yet, how they were made to be away from it and then the land grabbers in different forms and avatars ‘swallowed’ their land and houses.

She has taken care to document small to big daily life issues like civic conditions, roads, lanes by lanes, rations hops, voting venues, public transportation, banks, drinking water, water to use, schools, hospitals, post offices, telephone booths, clinics etc present in these settlements and their condition.

She has chosen to explain her point with the help of bar diagrams, maps and pictures.

On page 128 of her book Dr Shah writes “the way American Whites tortured and victimized Black Americans and disallowed them to live a lfie of dignity and civilized life, in a similar manner the 2002 Gujarat riots left minority community in a similar condition in Gujarat.

At the book release function held at Gujarat Vidyapeeth Dr. Shah presented her views in simple and through clear statements, which echoed the adverse and unwilling role of Gujarat police, Gujarat government in giving justice to the victims both for punishing the main culprits and to give them basic amenities and housing to live in till today after 13 years of the tragedy.

Dr. Shah also described as she documented it… the ugly and unbelievably sad picture of these victims and their dear ones living in utmost horrible living conditions in Ahmedabad itself which is being projected throughout the nation and the world as ‘developed city of a highly developed and model state of India’ and is being replicated in many other stated under the present government. She lamented the fact that till date no drinking clean water is available to these people who live very much in Ahmedabad city so to say. She showed with pictures how they are compelled to ‘buy’ the drinking water from the meagre source of income which speaks of their pathetic state of living.

Most of them do not have jobs or have lost their skills due to various factors mainly of being removed and dislocated from their original places of living.

Dr. Shah’s speech and words are based on the firsthand account of statements and reactions to her questionnaires in these pockets which she carried on for several months now and substantiated with pictures and power point presentation for her readers.

Mountain of filth which speaks of itself and the ghettoisation near the Mumbai Hotel area of Ahmedabad is not a hidden place. But, one needs guts to face this to believe how is it possible, to check our insensitive levels, but, Dr Shah did it which was not mandatory for her but she chose to do so, to let the world know what it is to live this life. She is not a politician or politics propagator but an ordinary middle class educated woman with a heart and mind which speaks for others and of others’ misery.

Dr. Shah said due to the ghettoisation of Muslims following the 2002 Gujarat riots, there has been shocking rise in religious obscurantism in the Muslim colonies, most of which were set up by Islamic non-government organizations in order to provide security to the riot victims.

Dr. Shah also explained that many of them have been forced to live here due to non-compliance of arrangement made for them by the state and authorities.

She also made an interesting statement as she said that despite all this darkness, the silver lining was that still they wanted to live with the mainstream and by the side of Hindu neighbours but in ‘safe’ areas which are a rare sight or not present in today’s Ahmedabad.

Perhaps the first book of its kind in Gujarati language, “Muslim Ghettoisation: Ek Karun Dastan” (Muslim Ghettoisation: A Tragedy), released at a formal function in Ahmedabad, has particularly noted that all the dozen resettlement colonies surveyed have “imposing mosques and madrasas attached to them, with all the necessary facilities”, in sharp contrast to the poor housing facilities in which the resettled Muslims live in sub-human conditions. Giving example of the type of "revivalism" that is prevailing in these resettlement colonies, Dr Shah quotes maulvis of the mosques as saying that “the Muslims had to suffer in the 2002 riots they failed to properly pray to the Allah.” Comments Dr Shah, “Following insecurity and fear because of the riots, there was a sharp rise in religious identity and a simultaneous rise in the grip of religious leaders on the resettlement colonies, with the community quietly and unwittingly supporting them.”

As a result of this, Dr Shah feels, the situation that has developed is such that, “while swearing by the name of religious freedom, these Muslims are unable to dissociate themselves from their communal framework.” Dr Shah’s book is based on a PhD thesis which she completed under the guidance of Dr. Anandiben Patel, head, social work department of the Gujarat Vidyapeeth. Based on spot interviews in 12 Muslim resettlement colonies of Ahmedabad, Sabarkantha and Anand districts set up after the Gujarat riots, Dr Shah says that ghettoisation has led to “sharp rise in religious polarization” with 92 per cent Muslims, who used to meet Hindus earlier, have no contact with them any more”.

Interesting observations made by Dr Shah in her book also take us to the pre-riots days of these very Muslims who had chance to live with their Hindu counterparts with whom they were brought up and played with.

She said these people who are today not exposed to the other community for days months and years now are totally isolated and are unaware of what is happening in other parts of the city …are left to themselves.

Earlier, they would celebrate Diwali and Holi with others, make items which were used by their Hindu neighbors and relatives, look at the temples and respect the sentiments and beliefs of others around. They lived with harmony and peace with their neighbours and friends and vice versa.

Published by ‘Gurjar Sahitya Prakashan’ and available at Sanskar Sahitya Mandir and ‘Gurjar Sahitya Bhavan’ in Ahmedabad, book book of Dr Damini Shah “Muslim Ghettoisation : A tragedy” is in Gujarati. It is priced at Rs. 247.

Scholarly remarks and short review of the book have been published on the last cover of the book by eminent social activists and men of words namely Writer and Journalist Prakash Shah and Prof Ghanshyam Shah.

Former Vice Chancellor of Gujarat Vidyapeeth Sudershan Iyengar and famous columnist and orator Prakash Shah also addressed the gathering on 24th February 2015.

Rafat Quadri, Editor : www.bilkulonline.com and BILKUL English Fortnightly newspaper

![]()

Evidently, the celebration of the St Valentine’s Day (popularly known as Valentine Day) has almost become a predictable routine in India; cards and gifts are exchanged and the entire atmosphere becomes radiant with red colour, love, romance and festivities. However, it is a different matter that most young persons who participate in this gaiety may not be aware of the history and various connotations of this Western festival.1 Nevertheless, the loud celebration of Valentine Day among the urban Indian youth, stubbornly defying antagonism of the opponents, requires an explanation. It cannot just be dismissed as an undesirable effect of market economy and capitalistic culture of the West or moral corruption caused by westernisation and globalisation. It is rather symptomatic of changing youth culture all over the world. However, particularly in India, apart from this kind of universalistic trend, it is also indicative of the wide-ranging changes taking place in traditional Indian social life, reflected by growing individualism among youngsters and the shaky arranged marriage system of India.

Evidently, the celebration of the St Valentine’s Day (popularly known as Valentine Day) has almost become a predictable routine in India; cards and gifts are exchanged and the entire atmosphere becomes radiant with red colour, love, romance and festivities. However, it is a different matter that most young persons who participate in this gaiety may not be aware of the history and various connotations of this Western festival.1 Nevertheless, the loud celebration of Valentine Day among the urban Indian youth, stubbornly defying antagonism of the opponents, requires an explanation. It cannot just be dismissed as an undesirable effect of market economy and capitalistic culture of the West or moral corruption caused by westernisation and globalisation. It is rather symptomatic of changing youth culture all over the world. However, particularly in India, apart from this kind of universalistic trend, it is also indicative of the wide-ranging changes taking place in traditional Indian social life, reflected by growing individualism among youngsters and the shaky arranged marriage system of India.