ગાંધીજીનું જીવન એ વિચારોની વિકાસયાત્રા છે. એમના જીવનની પળેપળ વિચારોનું અનુસંધાન છે અને તેનો વ્યાપ સંપૂર્ણ વિશ્વને આવરી લે છે. એકાંત વનમાં બેસી સાધના કરે તેવા ઋષિઓથી જુદી આ યુગપુરૂષની સાધના છે. તેમની સત્યની શોધની ચેતનાનો વિસ્તાર પ્રત્યેક માનવના હૃદય સુધી પ્રસરે છે. આ અતિશયોક્તિ નથી. જવાહરલાલ નહેરુએ લખ્યું છે, “ગાંધીજી લોકોની હૃદયવીણાના હરેક તારને જાણે છે, નિષ્ણાત સંગીતકારની જેમ કયે પ્રસંગે કયો તાર સ્પર્શવાથી તે યોગ્ય રીતે રણઝણી ઉઠશે તે જાણે છે.”

ગાંધીજીનું જીવન એ વિચારોની વિકાસયાત્રા છે. એમના જીવનની પળેપળ વિચારોનું અનુસંધાન છે અને તેનો વ્યાપ સંપૂર્ણ વિશ્વને આવરી લે છે. એકાંત વનમાં બેસી સાધના કરે તેવા ઋષિઓથી જુદી આ યુગપુરૂષની સાધના છે. તેમની સત્યની શોધની ચેતનાનો વિસ્તાર પ્રત્યેક માનવના હૃદય સુધી પ્રસરે છે. આ અતિશયોક્તિ નથી. જવાહરલાલ નહેરુએ લખ્યું છે, “ગાંધીજી લોકોની હૃદયવીણાના હરેક તારને જાણે છે, નિષ્ણાત સંગીતકારની જેમ કયે પ્રસંગે કયો તાર સ્પર્શવાથી તે યોગ્ય રીતે રણઝણી ઉઠશે તે જાણે છે.”

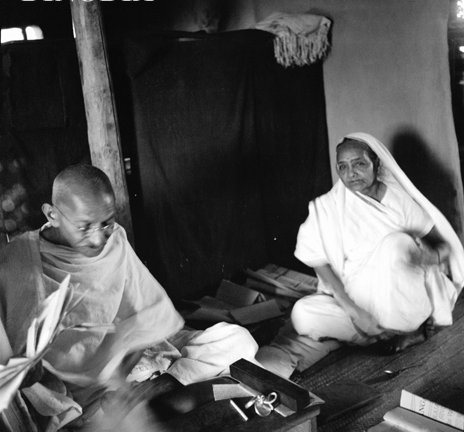

એ મહાત્મા તરીકે ઓળખાયા પરંતુ વાસ્તવમાં તો સામાન્યજન હતા, માનવ હતા. તેમણે એ જ રીતે વિચાર્યું અને ભૂલ પણ થઈ શકે એ સમજ સાથે એવું જ વર્તન કર્યું. માનવ કરી શકે અને જે મેળવી શકે તેવાં જ ડગ ભર્યા. મને યાદ છે ૧૯૪૮ની ૩૦મી જાન્યુઆરીનો દિવસ. હું નવ વર્ષની વયનો બાળક હતો છતાં ગાંધીજીના નિધનને દિવસે ડૂસકે ડૂસકે રડ્યો. મારું કુટુંબ, મારા પાડોશીઓ, રસ્તે ચાલતાં દરેક માણસને મેં રડતાં જોયાં. તે દિવસે જવાહરલાલ નહેરુએ રાષ્ટ્રને સંબોધી પ્રવચન કર્યું હતું તે મને જ્યારે સમજણ આવી ત્યારે જાણ્યું. આ પ્રવચનમાં તેમણે કહ્યું “The light has gone out of our lives” દેશવાસીઓએ તે દિવસે એક જ્ઞાનપ્રભાનો અસ્ત જોયો. પરંતુ આ પ્રભા એવી અસ્ત થાય તેવી પ્રભા ન હતી. લોકજીવનમાં સતત પ્રકાશ ફેલાવતી રહે તેવી શાશ્વત પ્રભા હતી. આ રાષ્ટ્રપુરુષ જનસમાજના હરેક સ્તરે વ્યાપ્ત બની રહ્યા. રાષ્ટ્રપિતા કહેવાયા. તેઓ કેવા યુગપુરુષ હતા તે મહાન વૈજ્ઞાનિક રોબર્ટ આઇન્સ્ટાઇનના આ શબ્દોથી જણાય છે; “આવો મહાન યુગપ્રવર્તક આ ધરણી પર હાલતો ચાલતો એક માણસ હતો તેવું ભાવિ પેઢી માનશે નહીં.”

અઢી લાખ વર્ષ પુરાણી માનવ સંસ્કૃિત છે. વિચારો તો થયા જ હોય. પાંચ હજારથી વધુ વર્ષ પુરાણા આપણા વેદ-પુરાણો. આ વિચારોના પ્રભાવ માનવ જીવનમાં વ્યાપ્ત હોય જ. સમય સાથે બદલાતી જીવનપ્રણાલી અને તેને અનુરૂપ વિચારો થતાં જ રહે. વિચારમાં ક્રાંતિ કહી શકાય તેવા સફળ અને નિષ્ફળ પ્રયોગો થતાં રહ્યાં. ગાંધીજીએ પણ સ્વાભાવિક રીતે જ એ અસરો ઝીલી. ગાંધીજીએ પોતાના જીવનકાર્યમાં આવી અસરો અંગે પોતાની આત્મકથા “સત્યના પ્રયોગો”માં ઉલ્લેખ કર્યો છે. ૧૯મી સદીમાં બે મહાન વ્યક્તિઓ માર્ક્સ અને ગાંધી. સમયની બે વિચારધારાઓ. જુદી જુદી છતાં સમાન. બન્ને વિચારધારા ઐતિહાસિક. પરંતુ તેનો ઉન્મેષ યુગપ્રવર્તક. આપણા મૂર્ધન્ય સાહિત્યકાર સ્વ. ઉમાશંકર જોશીની આ એક પંક્તિ આ મહાન વિચારકોના વિચારનો આધાર અને તેની સમાનતાને સ્પષ્ટ કરે છે. “ભૂખ્યા જનોનો જઠરાગ્નિ જાગશે, ખંડેરની ભસ્મકણી નવ લાધશે.”

ઔદ્યોગિક ક્રાંતિ પછીના સમયને વર્ણવતા એક અન્ય કવિ કહે છે: “ बारूद के ढेर पर बैठी है ये दुनिया.” આવા કપરા સમયમાં જે સંઘર્ષ હતો તે માનવ અને માનવ વચ્ચે, પરિસ્થિતિએ સર્જેલ વર્ગો વચ્ચે, રાજ્ય અને પ્રજા વચ્ચે, રાજ્ય અને અન્ય રાજ્યો વચ્ચે હતો. માર્ક્સ આ વર્ગવિગ્રહને સદંતર નેસ્તનાબૂદ કરવાના પક્ષમાં હતા. ગાંધીજી પણ વર્ગવિગ્રહ પરિસ્થિતિ જ સંઘર્ષ અને અસંતોષનું કારણ છે તે જાણતા હતા, પરંતુ તેઓ સંઘર્ષને અહિંસક સમજાવટ દ્વારા ઘટાડવાની તરફેણમાં હતા. હિંસાથી જ ટેવાયેલા વિશ્વને આ વિચાર કંઈક અવ્યવહારુ લાગતો હતો. “શમે ના વેરથી વેર.” એ ભારતીય વિચારધારા ગાંધીજીની રગરગમાં સ્થાયી હતી. ગાંધીજીએ આ સંઘર્ષના મૂળમાં બે તત્ત્વોની ઓળખ કરી. ઉદ્યોગોમાં મૂડીવાદીઓ અને મજૂર અને ખેતીવાડીમાં જમીનદાર અને ગણોત-ખેડૂતો. આ વર્ગોના સંઘર્ષને સમજાવટ અને પ્રેમથી ઓછો કરવા માટે અહિંસક માર્ગની હિમાયત કરી. જરૂર પડે સત્યાગ્રહનું શસ્ત્ર અજમાવવાનું સમજાવ્યું. આ નવતર પ્રયોગ હતો. માણસને માણસાઈ તરફ દોરવાનો પ્રયાસ હતો. જેની સામે વિરોધ છે તે સ્વયં અનિષ્ટ નથી પરંતુ પરિસ્થિતિજન્ય તેનામાં પ્રવેશી ગયેલ અનિષ્ટતાનો તેને પરિચય કરાવવાનો હતો. મૂડી અને શ્રમની સમાનતા સિદ્ધ કરવાનો હતો. શ્રમથી મૂડી નીપજે છે શ્રમનું મહત્ત્વ મૂડીથી વધુ છે તેની સમજ આપવાનો હતો. આવી સમજણનો અભાવ લાગે ત્યાં સત્યાગ્રહનો ઉપયોગ કરવાનો હતો. અસહકાર કરી અધિકાર માગવાનો હતો. અધમ વર્તાવ સામે સ્વમાન જાગૃત કરવાનો આ પ્રયોગ હતો. તેમની આત્મકથા સ્વરૂપ પુસ્તક ‘સત્યના પ્રયોગો’માં તેમણે કહ્યું છે, “મનુષ્ય દોષને ઝટ ગ્રહણ કરે છે. ગુણ ગ્રહણ કરવાને સારુ પ્રયાસની આવશ્યકતા છે.”

આવશ્યકતાને વ્યવહારમાં પરિવર્તિત કરવાનો અઘરો રસ્તો ગાંધીજીએ અપનાવ્યો. જ્યાં સંઘર્ષ જ હતો ત્યાં પ્રેમપૂર્વક સમજાવટનો રસ્તો લીધો. એક બાજુ દેશના સ્વાતંત્ર્ય માટે લડત અને બીજી બાજુ ખખડી ગયેલ સમાજ વ્યવસ્થામાં માનવીય ભાવ પ્રેરિત કરવાનું કામ. તે પણ નાનકડાં કસબામાં કે ગામ-શહેરમાં નહીં, પરંતુ ભારત જેવા વિશાળ દેશની કોટિ કોટિ જનતાના હૃદય સુધી પહોંચવાનું ભગીરથ કાર્ય હતું. માનસ પરિવર્તન કરવાની પ્રક્રિયા સાથે દેશ-કાળના સદીઓથી રૂઢ થયેલા અનેકવિધ સંદર્ભો જોડાયેલા અને જડાયેલા હોય. ‘સમૂળી ક્રાંતિ’ કરવાની હતી. આજ પણ વિચારીએ છીએ તો અશક્ય લાગે છે. જેને આપણે ભગવાન તરીકે પૂજીએ છીએ તે રામ, કૃષ્ણ, બુદ્ધ કે મહાવીર દ્વારા પણ થયું નથી. તે આ એક સૂકલકડી સામાન્ય પુરુષ દ્વારા સંપન્ન થયું. ભારત જ નહીં પૂર્ણ વિશ્વમાં આવી સિદ્ધિ એક પણ મનુષ્ય દાખવી શકેલ નથી. ગુણ-અવગુણ, ભૂલ-સમજ જે કંઈ એક સામાન્ય માનવીમાં હોય તેવા એક સાધારણ માણસે આ કર્યું.

સામે પહાડ જેવા પ્રશ્નો, પણ પાર કરવાની, નિશ્ચલ મનીષા લઈ નીકળેલા આ મહાત્માએ શું વિચારી આવું સાહસ કર્યું હશે. ગાંધીજીની શ્રદ્ધા હતી કે આખા જગતમાં જે સ્થૂળ સ્વરૂપે છે તે અને માનવ શક્તિ બન્ને પ્રાકૃતિક દેણ છે. માનવ સર્જિત સમાજ વ્યવસ્થા મુજબ સ્થાવર-જંગમ મિલકતોની માલિકી ભલે વ્યક્તિગત હોય પરંતુ જે પ્રકૃતિનું છે તેની ઉપર વાસ્તવમાં સામૂહિક માલિકી છે. તે માટે સામૂહિક વિશ્વાસની ભાવના કેળવવાની વાત ગાંધીજીએ કરી. “Social Trusteeship.” આવું ઓસડિયું સમાજ માટે ગુણકારી હતું પરંતુ કડવું હતું એટલે ગળે ઉતરવું મુશ્કેલ હતું. તેમ છતાં એ તર્કની સાથે અહિંસા માર્ગે સામાજિક ન્યાય પ્રાપ્ત કરવાનો ઉપાય સૂચવતો હતો. તેઓએ કહ્યું છે કે, “જે આપણી પાસે હોય તે અન્ય પણ ઉપલબ્ધ કરી શકે તેવી પરિસ્થિતિનું નિર્માણ થવું જોઈએ.” વર્ગ વિગ્રહને બદલે વર્ગ સહકારની સમજ વિકસાવવી જોઈએ. થોડાં શોષણખોરોનો નાશ કરવાને બદલે તેની સાથે અહિંસક અસહકાર કરવો જોઈએ. આવાં શિક્ષણ, સમજ અને જ્ઞાનનો પ્રસાર થવો જોઈએ. આનાથી શોષણકર્તાઓને પણ સમજ આવશે અને સહકારની ભાવના કેળવાશે. ગાંધીજીને માનવ જાત પર વિશ્વાસ છે. તેઓ કહેતાં કે “માનવ વૃત્તિ એ જ તેના વર્તનનું કારણ હોય છે.” અને તેમનો વિશ્વાસ હતો કે આ વૃત્તિઓ બદલી શકાય છે. યોગ્ય શિક્ષણ અને કેળવણીથી એ શક્ય છે. પ્રેમની ભાષા પ્રાણી માત્ર સમજે છે. આ પ્રેમનો માનવીય વિસ્તાર ગાંધીજીના વિચારથી વૈશ્વિક અપેક્ષા છે :

“I want to realize brotherhood and identify not merely with beings called human, but I want to realize identify with all life. Even with such being that crawl on this earth.” ( Mahatma Vol 2, p.253 )

ગાંધીજીના વિચાર એ પૂર્વગ્રહિત વિચારોનો વાડો નથી, એ તો વહેતી ધારા છે. માનવ વૃત્તિ અને વ્યવહારમાં પરિસ્થિતિજન્ય પરિવર્તન સતત થતું રહેવાનું. જે વિચાર ગઈકાલના ઇતિહાસમાં અને આવતીકાલની અપેક્ષાઓની સાથે સતત અનુસંધાન સાધતી રહે તેવી વિચારધારા છે. વિચારોના ઉન્મેષ અને આવિષ્કારોને આવકારતી વિચારધારા છે. એક પૂર્ણ સમાજ તરફની ગતિ મળે તેવી વિચારધારા છે. સત્ય, પ્રેમ અને અહિંસાના બળ પર માનવ માનવને સાંકળતી સર્જનાત્મક સમાજ રચવા માટેની વિચારધારા છે. સમગ્ર વિશ્વનો માનવસમાજ આ વિચારધારાના સામર્થ્યને સ્વીકારે છે. રામરાજ્ય આદર્શને આ સંદર્ભથી ઓળખાશે તો વિચ્છેદથી સંયોજન તરફ આપણે આગળ વધીશું.

ગાંધીજીએ કહ્યું છે: “આપણે ગુણગ્રાહી બનવું જોઈએ. હું સ્વયં ભૂલરહિત નથી તો અન્યની પાસે એવી અપેક્ષા કેવી રીતે રાખી શકું ?” સારા અને યોગ્ય વિચારો અંગે વધુમાં તેઓ કહે છે, “આપણા સકારાત્મક વિચારો એ આપણી વાણીમાં ઉતરે, વાણી આપણા વર્તનનું પ્રતિબિંબ પાડે , વર્તન આપણી આદત બને , આદત આપણા ગુણનો નિર્દેશ કરે અને તે આપણું ભાવિ બને.”

સત્તાના રાજકારણને પારદર્શક શુદ્ધતા તરફ દોરી જવા ગાંધીજીએ સાધ્ય અને સાધનની શુદ્ધિનો મંત્ર આપ્યો. માનવ સંબંધો સાથે સાંકળતા રાજકારણમાં તેની જરૂર સમજાવી. અન્યોના આધિપત્ય અને સત્તાથી સ્વતંત્ર થવા સાથે સત્ય સહિત પરંતુ હિંસા રહિત મુક્ત મનના સ્વાતંત્ર્ય તરફની દિશા બતાવી. સામાજિક અને આર્થિક કાર્યમાં અપરિગ્રહના સિદ્ધાંતોની હિમાયત કરી.

ભારતની પ્રજાની નાડ એક સાચા ભારતીય તરીકે તેમણે બરાબર જાણી હતી. સર્વ જાતિ, સર્વ ધર્મ અને સઘળાં સામાજિક અને આર્થિક સવાલોમાંથી એક સંયુક્ત સૂર ઉપજાવી અનેકતામાંથી ઐક્ય સાધવાનો ગાંધીજીનો આ પ્રયાસ હતો. ઇતિહાસનો ભાર લઈ જીવતી પ્રજાને ભારતીય અસ્મિતા તરફ જાગૃત કરવાનો પ્રયાસ હતો. રજવાડાઓ અને અંગ્રેજ સત્તામાં સપડાયેલ પ્રજામાં એવી ચેતના ભરવાની હતી કે લોકો પોતાની સત્તા-લોકશાહીના મૂલ્ય સમજી શકે. રામ, કૃષ્ણ, બુદ્ધ અને મહાવીરના આ દેશમાં આધ્યાત્મિક મૂલ્યો તો રગરગમાં હતા. દેશની એ જ તો મૂડી અને ઓળખ હતી. લોકોને સારપ, પ્રેમ, સદ્દવર્તન સત્ય, અહિંસા, અપરિગ્રહના આદર્શો શીખવા જવાની જરૂર ન હતી. ગાંધીજી એ જ આદર્શોને સ્વાતંત્ર્ય લડતના હથિયાર બનાવ્યાં. લોકસમૂહને ગાંધીજી પોતાના સ્વજન લાગ્યાં. તેમની વાત પોતાના મનની વાત લાગી. કરોડોના કંઠમાં આ દેશ મારો છે ગૂંજવા લાગ્યો. કોઈ પણ અંગત સ્વાર્થ વગર પોતાની જાતને સ્વાતંત્ર્ય યજ્ઞમાં હોમી દેવા તત્પર ગાંધીનો બોલ દેશનો અવાજ બની ગયો. ગાંધીજી વિદેશી સત્તાને દૂર કરવા સાથે એવું રાષ્ટ્ર ઈચ્છતા હતા કે જ્યાં વૈમનસ્ય નહીં સ્નેહભાવનું આધિપત્ય હોય. ગાંધીજી કદાચ પૂર્ણપણે આ પામી ન શક્યા કારણ કે અમાપ વૈવિધ્યના આ દેશમાં કેટલાંક એવાં તત્ત્વો પણ હતાં કે સ્વાતંત્ર્ય મળ્યા પછી તેમના વ્યક્તિગત હિતોની તેમને વધુ પરવા હતી. ગાંધીજીનું જીવન એ જ તેમનો સંદેશ છે તેવું તેમનું વિધાન સમજવા જેવું છે. તેઓ ‘સત્યના પ્રયોગ’ કહે છે તે પાછળ જે અભિપ્રેત છે કે એક મનુષ્યે જીવનભર સત્ય તરફ પહોંચવા પ્રયત્ન કર્યા છે. તેઓનો ક્યાં ય એવો દાવો નથી કર્યો કે તેઓ અંતિમ સત્યે પહોંચી ગયા છે. આદિનાથ પ્રભુએ પણ કહ્યું છે કે “પ્રબુદ્ધ થવું એ દરેક માનવીની ગતિ હોવી જોઈએ. અન્ય વિચાર આપી શકે પરંતુ તે પ્રાપ્ત કરવા મેં જેમ પ્રયત્ન કર્યા છે તેમ દરેક કરે ત્યારે જ મતિ પ્રમાણે સ્થિતિ પામી શકે”. એટલે જીવન સાથે સતત પ્રવાહની જેમ વિચાર કરવા જોઈએ. વિચાર એ શક્તિ છે. વ્યક્તિ વિચારે અને તે વ્યક્ત કરે અને આપણા વિચાર મુજબ તે સ્વીકાર્ય લાગે તો અવશ્ય સ્વીકારવા જોઈએ પરંતુ સમજવું જોઈએ કે ત્યાં અંતિમ નથી. આપણા સમાજનો મોટો ભાગ સ્થિર થઈ જઈ વ્યક્તિપૂજા કરતા થઈ જતાં હોય છે. વિચાર કરનાર વ્યક્તિ આપણા જેવો જ માણસ છે. એટલે ગાંધીશબ્દ કોઈ સ્થગિત વિચાર નથી જીવન સાથે અનુસંધાન કરતી વિચારધારા છે. હા! ગાંધી નામની આ વ્યક્તિએ જે કામ કર્યું છે તે એક જ જીવનમાં એક જ વ્યક્તિએ કઈ રીતે કર્યું તેનું આશ્ચર્ય તો મને પણ છે. અત્યંત અભિભૂત પણ છું. સાથે એ પણ જાણું છું કે તેઓ પૂજાપુરુષ નહીં પરંતુ પ્રેરણાપુરુષ – યુગપુરુષ હતા. એમનો માનવજાત તરફનો અતૂટ વિશ્વાસ તેમના આ શબ્દોમાં પ્રતીત થાય છે. “You must not lose faith in humanity. Humanity is an ocean; if a few drops of the ocean are dirty, the ocean does not become dirty.”

મારા એક કાવ્યની થોડી પંક્તિઓમાં આ બાપુને સંબોધી આશ્ચર્ય વ્યક્ત થયું છે તે પ્રસ્તુત છે. શીર્ષક છે:

એવા તો કેવાં તમે …

એક ના અનેકવાર દીધાં અમે ને તમે

હસતાં હસતાં જ એ લીધાં ?

એવાં તો કેવાં તમે ‘બાપુ’ જાદુગર

અમૃતની જેમ ઝેર પીધાં.

વાવડ હતા જરૂર મોતના સિવાય ત્યાં

મળવાનું અંગત જરાય ના,

કોટિ કોટિ લોક જેની હાકલથી મારગમાં

ઓઢી કફન ઉભરાયાં.

એવાં તો કેવાં તમે ‘બાપુ’ બાજીગર

મૃત્યુને નામ અમર દીધાં.

બાપુને ૨જી ઓક્ટોબર ૨૦૧૬ના શ્રધાંજલિ આપતા, ૧૯૪૮ના જાન્યુઆરીમાં ઊભરાયેલા આંસુ આજ પણ આંખમાં છે. બાપુના પડછાયામાં અંધારાનું વર્ણન કરી રાજી થતાં માનવો પણ છે. બાપુ જીવ્યા છે તે મુજબ નહીં પરંતુ તેમણે કેવું જીવવું જોઈતું હતું તેવી સુફિયાણી વાતો કરનારાઓ પણ છે. તેમાં કોઈ આશ્ચર્ય નથી. ભારતના વેદ અને પુરાણોએ સંસ્કૃિતનું નિર્માણ કર્યું. અમુક ભાવછાયાઓ મુજબ તેના અર્થઘટનો, બહારના તત્ત્વો અને આક્રમણોની અસર અને નિર્બળ પ્રતિકારમાં સહિષ્ણુતાના ગુણની પ્રતિષ્ઠાએ ગુલામીના સ્વીકારની વૃત્તિ આવી. આવાં પ્રબળ અનિષ્ટોને નાબૂદ કરી રાષ્ટ્રનિર્માણ કરવાનું લગભગ અશક્ય કામ “નબળા શરીરમાં વસતા બળવાન આત્મા”એ કર્યું. સ્વતંત્રતા માત્ર નહીં સ્વસ્થ વિચાર તરફ લઈ જનાર મહાત્મા ગાંધીને આપણે રાષ્ટ્રપિતાનું બિરુદ આપ્યું છે. તેથીએ વિશેષ તો આ દેશના એક વિશ્વકર્મા-સ્થપતિ છે.

બાપુ ! તમે આજ પણ અમારા માટે કદી ન અસ્ત થાય તેવો પ્રકાશપુંજ છો. આપને નમુ છું બાપુ !

અસ્તુ.

e.mail : Kanubhai.suchak@gmail.com

3 Vivek,185 S V Road, Vile Parle [West], Mumbai – 400 056

![]()

ચંપારણ્યનો ગળીવિરોધી સત્યાગ્રહ ઈ.સ ૧૯૧૭માં થયો હતો. ગાંધીજી ૧૯૧૫માં દક્ષિણ આફ્રિકાથી પરત ફર્યા. તે સમયે તેઓ મહાત્મા તરીકે ઓળખાતા નહોતા. દક્ષિણ આફ્રિકામાં બાવીસ વર્ષના સમયગાળા દરમિયાન તેમણે બૌદ્ધિક આદર્શોને વ્યવહારિક રૂપ આપ્યું હતું. રસ્કિનની પુસ્તિકા વાંચી પોતાની જીવનશૈલી બદલી હતી. ફિનિક્સમાં આશ્રમ સ્થાપી તેમણે ખેડૂતોની જીવનશૈલી અપનાવી હતી. દક્ષિણ આફ્રિકાની લડતોને કારણે કાચું લોખંડ પોલાદમાં ફેરવાઈ ચૂક્યું હતું. વ્યક્તિગત જીવન અને માનવસંબંધો અંગેનું વ્યાપક જીવનદર્શન તેમનામાં વિકસિત થયું હતું. તેમ જ સમાજની અર્થવ્યવસ્થા અને સરકારના કર્તવ્ય અંગે પણ તેમના વિચાર ખૂબ સ્પષ્ટ હતા.

ચંપારણ્યનો ગળીવિરોધી સત્યાગ્રહ ઈ.સ ૧૯૧૭માં થયો હતો. ગાંધીજી ૧૯૧૫માં દક્ષિણ આફ્રિકાથી પરત ફર્યા. તે સમયે તેઓ મહાત્મા તરીકે ઓળખાતા નહોતા. દક્ષિણ આફ્રિકામાં બાવીસ વર્ષના સમયગાળા દરમિયાન તેમણે બૌદ્ધિક આદર્શોને વ્યવહારિક રૂપ આપ્યું હતું. રસ્કિનની પુસ્તિકા વાંચી પોતાની જીવનશૈલી બદલી હતી. ફિનિક્સમાં આશ્રમ સ્થાપી તેમણે ખેડૂતોની જીવનશૈલી અપનાવી હતી. દક્ષિણ આફ્રિકાની લડતોને કારણે કાચું લોખંડ પોલાદમાં ફેરવાઈ ચૂક્યું હતું. વ્યક્તિગત જીવન અને માનવસંબંધો અંગેનું વ્યાપક જીવનદર્શન તેમનામાં વિકસિત થયું હતું. તેમ જ સમાજની અર્થવ્યવસ્થા અને સરકારના કર્તવ્ય અંગે પણ તેમના વિચાર ખૂબ સ્પષ્ટ હતા.