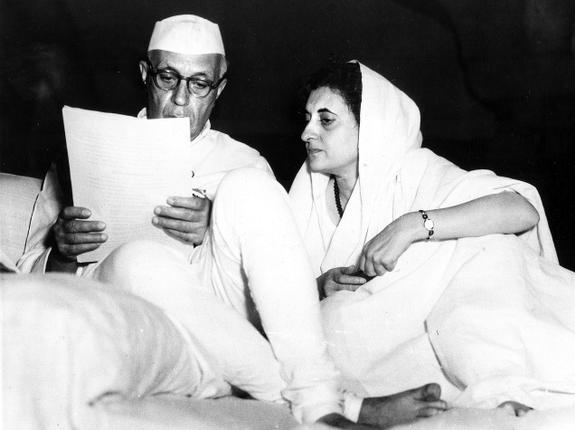

The memory of great men often fades with times: The Gandhi generation has gone and the Nehru generation is passing rapidly. It is, therefore, important to preserve the legacy of these remarkable leaders so that future generations remain aware of their contribution to achieving and consolidating our dearly won freedom.

The memory of great men often fades with times: The Gandhi generation has gone and the Nehru generation is passing rapidly. It is, therefore, important to preserve the legacy of these remarkable leaders so that future generations remain aware of their contribution to achieving and consolidating our dearly won freedom.

We now take our Independence for granted, but it is often forgotten that at least a million people were brutally murdered in the process and as many as ten million uprooted from their homes on both sides in what was probably the largest mass migration in human history. To stabilise and consolidate the situation after Independence required statesmanship of a high order, and the Cabinet, led by Jawaharlal Nehru and including stalwarts like Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel as deputy prime minister and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, was able to do this. The first great achievement of Nehru after Independence, therefore, was to hold the ship of state firm amid the turbulent waters of the Partition process, despite predictions of the prophets of doom, including Winston Churchill, who said that after the British left India would Balkanise and break up into a dozen units.

The second great task was, after centuries of foreign rule, for India to get itself a new Constitution. Himself an impeccable parliamentarian, Nehru not only took a keen interest in the framing of the Constitution but also attended Parliament for long hours, answered questions and in particular spoke on foreign relations, a portfolio he had kept with himself.

After Partition, India was a patchwork quilt consisting of what used to be called ‘British India’ and hundreds of princely states ranging from large ones like Jammu and Kashmir, Hyderabad, Mysore, Baroda and Gwalior to tiny principalities. Knitting these separate units into a single State was a massive task, the main credit for which goes to Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. The non-violent integration of so many feudal states into a democracy was surely unprecedented in world history. Although Nehru left this area mainly to Patel, he closely monitored the whole process and, despite his strong anti-feudal feelings, he realised the importance of seeking the cooperation of the ruling princes.

Nehru was deeply committed to the development of science and what he called the scientific temper, an attitude devoid of superstition and blind faith. For this purpose he had the foresight to set up the Indian Institutes of Technology in major cities around the country.

The underpinning of the whole saga of independent India has been an unwavering commitment to democracy. Nehru, steeped in the liberal democratic traditions of Britain, the republican ideals of the French Revolution and the socialist vision of the Russian Revolution, was a firm votary of democracy. It is interesting to recall an anonymous letter that appeared in the late 1930s in the Modern Review saying:

“(Nehru) has all the makings of a dictator in him — vast popularity, a strong will directed to a well-defined purpose, energy, pride, organizational capacity, ability, hardness, and with all his love of the crowd, an intolerance of others and a certain contempt of the weak and the inefficient…From the far north to Cape Comorian he has gone like some triumphant Caesar, leaving a trail of glory and legend behind him…(I)s it his will to power that is driving him from crowd? His conceit is already formidable. He must be checked, We want no Caesars.” Astoundingly, he had written that article pseudonymously!

A major triumph consisted in his leadership of what came to be known as the Non-Aligned Movement, along with President Nasser of Egypt, President Tito of Yugoslavia and Archbishop Makarios of Cyprus. President Sukarno of Indonesia was also involved, although his actions were often erratic.

His greatest tragedy, of course, was China. Nehru believed that the new China, which emerged after the overthrow of the previous regime, and which had suffered long periods of colonial domination, would be a natural ally of India in the post-colonial period.

Despite the long undemarcated border with China, Nehru was convinced that differences could be sorted out in a spirit of goodwill and mutual adjustment. As it turned out he underestimated the Chinese drive for power. The whole Chinese disaster has been widely researched and written up, except that the Henderson Brooks’ report on the debacle has still not been made public.

The whole episode caused Nehru immense shock and embarrassment. He was obliged to sack his favourite Krishna Menon. The failure of the whole Panchsheel approach to China was something that shattered Nehru’s psyche. He never really recovered from this setback and passed away within less than two years thereafter. Despite the Chinese debacle, the Indian Foreign Service today owes its origin to him, because after the British had left he had to build the whole service virtually from scratch.

Another area in which he faced difficulties, of course, was the issue of Jammu and Kashmir. Suffice it to say, after my father (Maharaja Hari Singh) had signed the Instrument of Accession in the wake of the Pakistani invasion, the much-criticised reference to the United Nations once again flowed from his idealism and his firm belief, strongly encouraged by Lord Mountbatten, that the newly created international body would clearly identify the aggressor and take steps to have the invasion withdrawn.

Nehru was a bitter opponent of religious fundamentalism, whether Muslim or Hindu. There is a view that Nehru’s attitude towards religion tended to be dismissive, and that despite all that he has written in the Discovery of India, he was never at ease with organised religion. This was largely true, though in his writings he did pay rich homage to the Upanishads and Shankaracharya, and he was particularly impressed by the Buddha and his teachings.

The people of India held Nehru in special affection which is reflected in his last will and testament, where he says: “If any people choose to think of me, then I should like them to say this was a man who, with all his mind and heart, loved India and the Indian people. And they, in turn, were indulgent to him and gave him of their love most abundantly and extravagantly.”

I will close with another quotation that could appropriately be directed towards Nehru. It is from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar and refers to Brutus. But it could very well apply to Nehru. “His life was gentle, and the elements so mixed in him that nature might stand up and say to all the world this was a man.”

Karan Singh is a Rajya Sabha MP

The views expressed by the author are personal

http://www.hindustantimes.com/comment/analysis/nehru-held-the-ship-of-state-firm-amid-the-turbulent-waters-of-partition/article1-1285852.aspx#sthash.WqXFF1Iy.dpuf

courtesy : “The Hindustan Times”, November 13, 2014

![]()

Certain segments in our society are engaged in a futile and odious comparison between the tall leaders of our freedom struggle; some others are out to diminish Jawaharlal Nehru’s stature and repudiate his legacy. Without being swayed by the rhetoric of the publicists or the ill-informed mediamen, we need to bolster Nehru’s position as the second best leader after the Mahatma. “Swachh Bharat” will not do. Whosoever is in power, Nehru’s memory must be kept alive in the interest of our democratic and secular values. Students of Indian history, on the other hand, will benefit from his writings, which embrace the creative thrust and splendour of the Continental and Indian civilisation.

Certain segments in our society are engaged in a futile and odious comparison between the tall leaders of our freedom struggle; some others are out to diminish Jawaharlal Nehru’s stature and repudiate his legacy. Without being swayed by the rhetoric of the publicists or the ill-informed mediamen, we need to bolster Nehru’s position as the second best leader after the Mahatma. “Swachh Bharat” will not do. Whosoever is in power, Nehru’s memory must be kept alive in the interest of our democratic and secular values. Students of Indian history, on the other hand, will benefit from his writings, which embrace the creative thrust and splendour of the Continental and Indian civilisation.