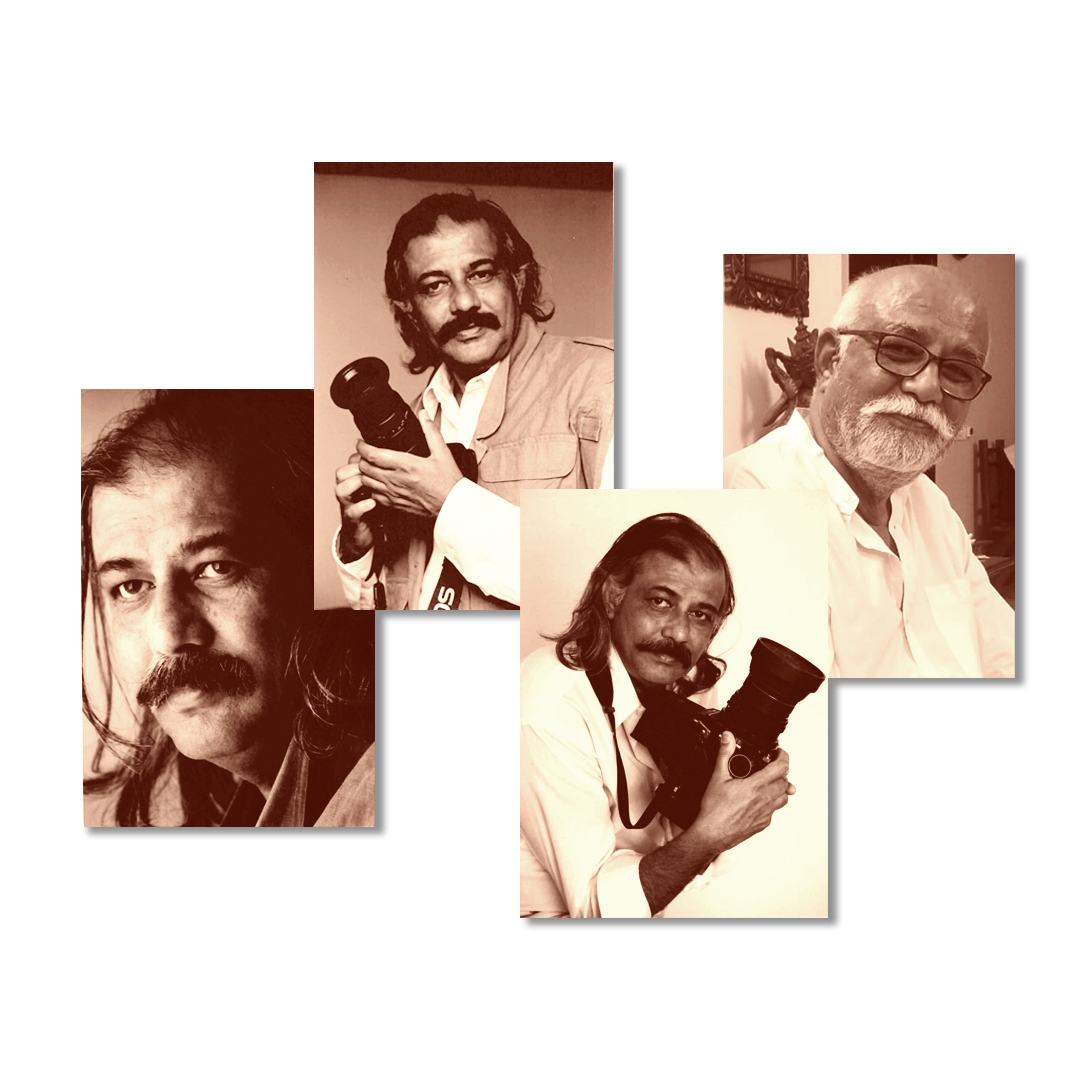

I first met Dhairyakant “Titi '' Chauhan about twenty-five years ago. My initial impression of him was that he was a man of few words, shy, introvert and somewhat reserved. To get him to speak, one would have to needle him, ask questions. His answers would always be cryptic and not forthcoming. However, his vivacious wife Darshana, made up for him. She would do all the talking for him and even answer questions that were addressed to Titi!

It took some time for me to learn that Titi was a distinguished photographer and had a sizable collection of photographs that he had exhibited in India. After some cajoling, he agreed to show a sample of his photographs. One look at those pictures and I could see his artistic genius. I could also see that this man of few words was eloquent in his art. His work spoke volumes. His abundant artistic talent showed through his photographs that depict how Gujarat’s nomadic and pastoral tribes were struggling to preserve their way of life in a fast-changing world. In essence, Titi was telling their poignant story through the lens of his camera.

Two distinctive elements of Titi’s photography were lighting and composition. He always preferred using natural light. He would patiently wait for hours to get just the right light and also an appropriate angle that would show the essence of whatever he was photographing. He also had an eye for exact composition–what to include and what not to.

I immediately offered to help him arrange an exhibition at the Gandhi Memorial Center, a mecca of Indian arts and culture in Washington, DC. The exhibition called, “India’s Original People,” opened in February, 2010 with rave reviews from the members of the Center. Soon after that his work was exhibited at the headquarters of the World Bank in Washington. I also attended Titi’s exhibition at the Nehru Center in London that was organized with help of Vipool Kalyani, a good friend and the distinguished leader of Britain's Gujarati Diaspora.

To expose Titi’s work to the larger Washington arts community, we also tried to explore the possibility of holding an exhibition at the Smithsonian, the world renown museum that would have given Titi national as well as international visibility. But it was not to be. Titi decided to go back to India before the Smithsonian exhibition could be arranged. His heart was in India and with the nomads of Gujarat with whom he wanted to do more work.

In many ways Titi’s American sojourn was a challenging adventure. He cheerfully met the artistic demands of land and people different from what he had known in India. He took every opportunity to travel far and near in the United States. He was constantly searching for new objects and themes to focus on for his photography. He was undaunted by the challenge of mobile phone technology that made it easy for any one to be a photographer. Titi’s faith in photography never wavered. He was a confident artist who knew that as everyone who writes doesn’t become a writer, similarly anyone who whips out a mobile phone to take a picture doesn’t become a photographer.

In recent years, in addition to photography, Titi turned to farming and devoted his considerable energy to grow a special brand of mango that he would lovingly share with all who would visit his farm in Gujarat. Every time I go to India, I would make it a point to visit Titi and Darshana at their farm as well as in their fashionable flat in Ahmedabad. Titi would lovingly cook vegetables he would have grown in his farm. We would sit for hours at the dinner table and reminisce about our days in Washington and also talk about photography projects he was dreaming about.

Pandemic like Covid-19 strikes indiscriminately. In losing Titi to this unyielding epidemic, Darshana has lost her devoted husband, many of his admirers like me have lost a generous friend and Gujarat has lost one of its finest photographers for whom photography was life’s meaning and mission. I will always cherish my friendship with him and miss Titi, a good hearted man of gentle manners, simplicity and sincerity.

————————————————————————————————–

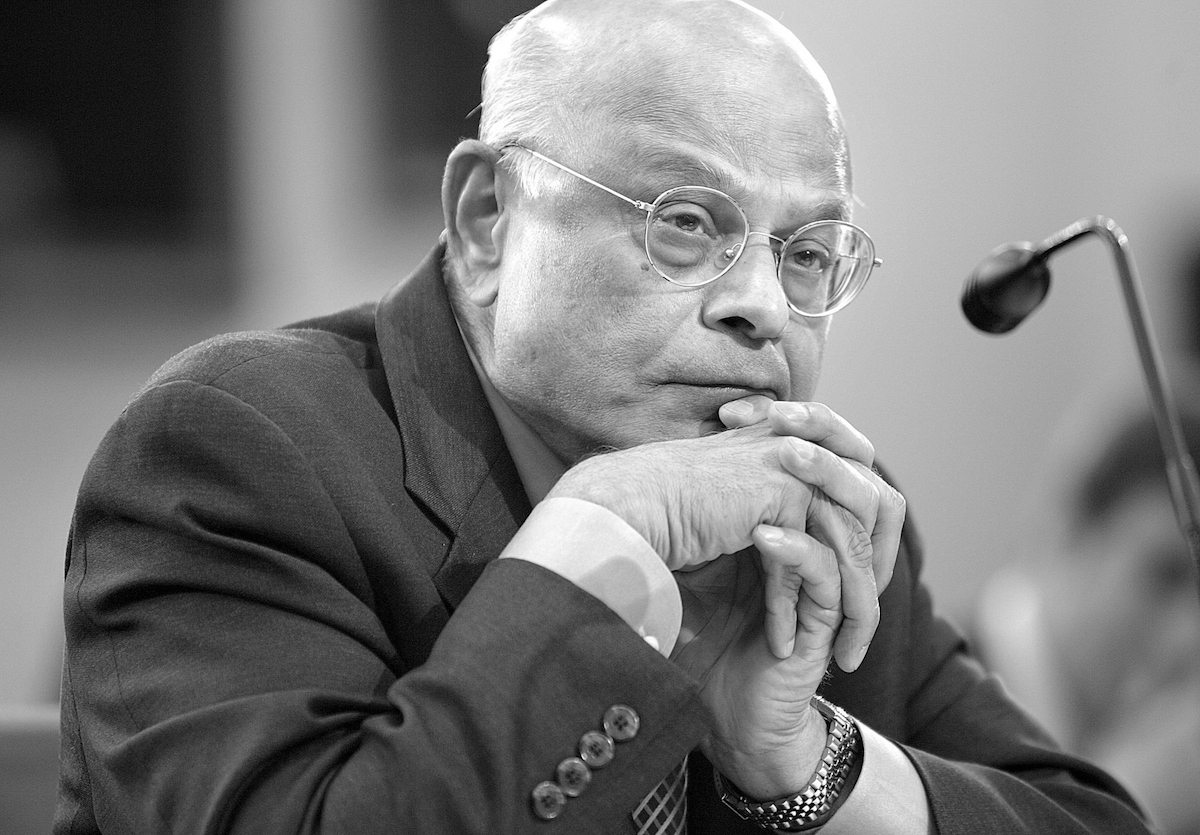

Natwar Gandhi is former Chief Financial Officer (2000-2013) of Washington, DC. Presently, he consults with the World Bank in its efforts to create financially sustainable cities around the world. He is also a member of Board of Trustees of Gallaudet University and a member of Boards of Honorary Trustees at Shakespeare Theater Company as well as Arena Stage.

Photo courtesy : http://www.dhairyakanttiti.art)

Dhairyakant Chauhan's wife Darshana Vyas has put together a wonderful website (http://www.dhairyakanttiti.art) in his memory.

![]()

That like their contemporary poets Sadanand Rege, Grace, Arati Prabhu, Namdeo Dhasal and Narayan Surve, Chitre and Kolatkar too created a space for their sensibility and an independent readership in Marathi language. Although their poetry is loaded with the cultural references to Maharashtra like Dnyaneshwar, Tukaram, Jejuri, and Panhala, the Indian and Western ideologies emerged outside Maharashtra have also been assimilated in it and they are quite clear. Both these poets are the best examples of the influence of two hundred years encounter and hybridization of English and Marathi after Mardhekar. Mardhekar, Chitre and Kolatkar are the most significant Marathi poets of twentieth century who assimilated the Western literature and style but never forgot their native poetic tradition.

That like their contemporary poets Sadanand Rege, Grace, Arati Prabhu, Namdeo Dhasal and Narayan Surve, Chitre and Kolatkar too created a space for their sensibility and an independent readership in Marathi language. Although their poetry is loaded with the cultural references to Maharashtra like Dnyaneshwar, Tukaram, Jejuri, and Panhala, the Indian and Western ideologies emerged outside Maharashtra have also been assimilated in it and they are quite clear. Both these poets are the best examples of the influence of two hundred years encounter and hybridization of English and Marathi after Mardhekar. Mardhekar, Chitre and Kolatkar are the most significant Marathi poets of twentieth century who assimilated the Western literature and style but never forgot their native poetic tradition. It was in early nineteenth century the young teachers in Hindu College of Kolkata started the practice of using English to describe Indian scenario in poetry. With the inclusion of English language and literature in the curriculum of schools and colleges, this tendency got spread outside Kolkata too. Due to the English translation of his works as Rabindranath Tagore received the Nobel Prize for literature in the early twentieth century, the contemporary poetry was profusely translated from Indian languages into English. Emergence of modernity in literature in the post-Independence period stylistically breathed a fresh air into Indian English poetry. Recognition of English as an official language of India by Indian Constitution boosted up the tendency to prefer English language for creative writing though the writers lived in India. In the history of Indian poetry in English spanning over two hundred years the names of five to six poets are inevitably mentioned and after the publication of Jejuri in 1976 Arun Kolatkar is one of them. Moreover, Chitre's reputation has also been increasing in this canon. Publication of Nissim Ezekiel's anthology of poems A Time to Change (1952) has been considered as the beginning of modernity in Indian English poetry. During these four decades Ezekiel, Ramanujan, Kolatkar and Jayant Mahapatra are considered to have contributed substantially to this kind of poetry. Their poems are included in the university curriculum of several countries. And wherever English education has reached, these poets are known, may be at the introductory level, to the academic world of teachers and students. In recent times, Chitre's name is also getting associated with other prominent poets. Therefore, these two important Marathi poets of ours could have certainly been recognized as the significant poets in Indian English and therefore, significant Marathi poets too.

It was in early nineteenth century the young teachers in Hindu College of Kolkata started the practice of using English to describe Indian scenario in poetry. With the inclusion of English language and literature in the curriculum of schools and colleges, this tendency got spread outside Kolkata too. Due to the English translation of his works as Rabindranath Tagore received the Nobel Prize for literature in the early twentieth century, the contemporary poetry was profusely translated from Indian languages into English. Emergence of modernity in literature in the post-Independence period stylistically breathed a fresh air into Indian English poetry. Recognition of English as an official language of India by Indian Constitution boosted up the tendency to prefer English language for creative writing though the writers lived in India. In the history of Indian poetry in English spanning over two hundred years the names of five to six poets are inevitably mentioned and after the publication of Jejuri in 1976 Arun Kolatkar is one of them. Moreover, Chitre's reputation has also been increasing in this canon. Publication of Nissim Ezekiel's anthology of poems A Time to Change (1952) has been considered as the beginning of modernity in Indian English poetry. During these four decades Ezekiel, Ramanujan, Kolatkar and Jayant Mahapatra are considered to have contributed substantially to this kind of poetry. Their poems are included in the university curriculum of several countries. And wherever English education has reached, these poets are known, may be at the introductory level, to the academic world of teachers and students. In recent times, Chitre's name is also getting associated with other prominent poets. Therefore, these two important Marathi poets of ours could have certainly been recognized as the significant poets in Indian English and therefore, significant Marathi poets too. A question often raised among Gujarati NRIs at parties and elsewhere is: How to preserve the Gujrati culture if children don’t learn the language of their parents and grandparents? The obvious reason children don’t speak Gujrati, much less read or write, is that adults don’t speak the language at home. Sadly, this is true among the well educated families in India as well. It is the same everywhere: in colleges and universities, at public gatherings, as well as in conversations with friends and acauaitances. Pick up any issue of Chitralekha, a widely circulated Gujarati magazine and you will see in it a language that is an easy mixture of Gujarati and English with English words sprinkled almost every other sentence. There is even a name for this new language–Gujlish. It is prevalent all over TV and radio programs and in print media. Listen, for example, the popular Gujarati radio show by RJ Devaki just for a few minutes and you will hear conversations that are in half Gujarati and half English and sometimes mostly in English while her audience consists mostly of Gujaratis.

A question often raised among Gujarati NRIs at parties and elsewhere is: How to preserve the Gujrati culture if children don’t learn the language of their parents and grandparents? The obvious reason children don’t speak Gujrati, much less read or write, is that adults don’t speak the language at home. Sadly, this is true among the well educated families in India as well. It is the same everywhere: in colleges and universities, at public gatherings, as well as in conversations with friends and acauaitances. Pick up any issue of Chitralekha, a widely circulated Gujarati magazine and you will see in it a language that is an easy mixture of Gujarati and English with English words sprinkled almost every other sentence. There is even a name for this new language–Gujlish. It is prevalent all over TV and radio programs and in print media. Listen, for example, the popular Gujarati radio show by RJ Devaki just for a few minutes and you will hear conversations that are in half Gujarati and half English and sometimes mostly in English while her audience consists mostly of Gujaratis.