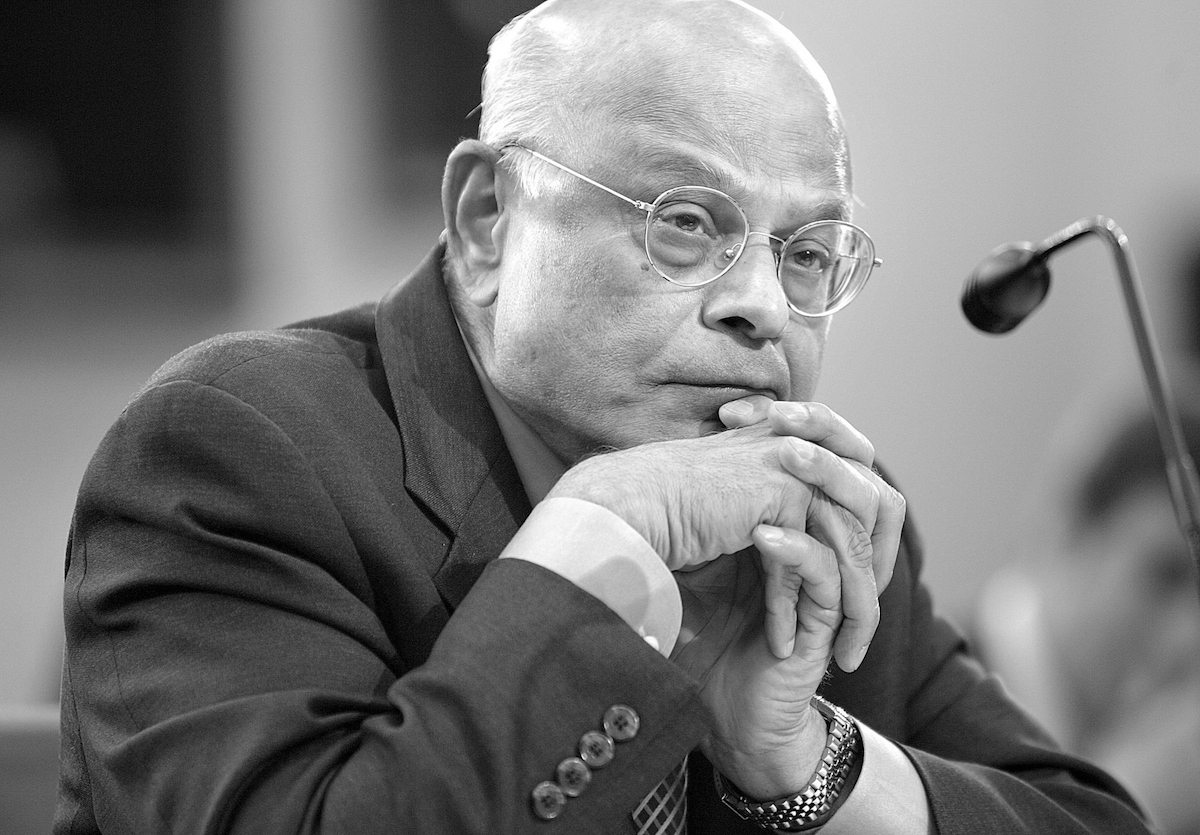

Professor Howard Spodek, the distinguished historian and a chronicler of Ahmedabad, has raised an interesting issue about the continuity of Hindu culture and religion in the United States. Recalling his after-school Hebrew school from second grade through the end of high school that instilled in him the essence of Judaism, asks: What do we “know about Indian cultural education, including school, camps, and temple (or mosque, or gurudwara) programs for first- and second-generation kids (also maybe for adults) coming from India?”

Professor Howard Spodek, the distinguished historian and a chronicler of Ahmedabad, has raised an interesting issue about the continuity of Hindu culture and religion in the United States. Recalling his after-school Hebrew school from second grade through the end of high school that instilled in him the essence of Judaism, asks: What do we “know about Indian cultural education, including school, camps, and temple (or mosque, or gurudwara) programs for first- and second-generation kids (also maybe for adults) coming from India?”

There have been sporadic attempts to educate children in the cultural and religious tradition of Hinduism. However, I do not know of any sustained efforts to do so in the manner of Jewish tradition of encouraging children to attend a Hebrew school where they would learn the language, culture and religion. The Jewish emphasis on religious education is rooted in their history as a perennially persecuted minority. To persevere through persecution and the perpetual wandering, the Jews had to come up with a survival strategy. It was the preservation of religion and culture.

The famous 12th century Jewish philosopher Maimonides called Jews the chosen people and asked them to keep the Torah and admonished them that God would punish those who transgressed it. (See below the loose translation of my Guajarati poem on Jews.) Hindus never faced such perennial persecution. Even during the worst excesses of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in the 17the century, the Hindus never suffered like the Jews. Further, they always had a home that the Jews never had until the establishment of Israel in 1948.

Jews have a sense of history and a historical perspective that Hindus generally lack. Again, to quote Maimonides, for Jews “history is holy, and memory a priceless treasure, because we suffer and suffer and still strive and survive.” Hindus’ sense of historical memory was largely given to them by the British historians. Most of the history of India was written only after the British came to India. Recall, for example, the pioneering work of Sir William Jones, the great Indologist, who founded Asiatic Society in 1784.

Further, unlike Judaism, Hinduism has been splintered into numerous branches. Thus, for example in Washington, DC, we have the Jains, the Swaminarayanis, the Vaishnavites, the Shaivats, just to name a few. Each claim to be unique and different from others, yet they all call themselves Hindus. Most of them have their own separate places of worship and conduct some sort of weekend religious services including education. However, these efforts are not integrated, systematic or sustained.

Hindus are also fragmented along the linguistic lines. There are many linguistic groups such as Gujarati, Marathi, Hindi, Bengali, Sindhi, Telugu, Tamil, etc. in India as well as places where they migrated. Each language group has its own social organization that arranges regular events and gatherings. There are even literary associations that hold periodic meetings. These associations attempt to conduct linguistic education; however, these efforts again are not sustained and have very little lasting consequences. These associations cater mostly to the first-generation immigrants to soothe their social isolation from mainstream American society.

Yes, the Hindus do build big temples, witness for example Swaminarayan temples in Chicago, Houston, Atlanta, Robbinsville, NJ and other places where there is a large concentration of Indians. These temples are built to calm religious anxieties of the first-generation immigrants. They are places of worship, social gathering as well as venues of occasional revival meetings when renowned Gurus or Swamis visit from India. However, the Hindu children who are born and raised in the United States are blissfully indifferent or ignorant of religious activities of the temples.

Islam as a religion can be practiced in widely different social environments. Hinduism on the other hand is integrated with Hindu society and the way of life. How can we separate such staple religious festivals as Ganesh Chaturthi, Rama Navami, Navratri or Diwali from their larger societal context? The Hindus who migrated to Africa over the last two hundred years have been able to maintain their religion but only by creating a society separate from the host country. They did not assimilate with local communities and maintained their separate social life. However, they paid a heavy price for such isolation. Recall what happened to Hindus, particularly Gujaratis, in Uganda in 1972 under the regime of Idi Amin.

Creating a separate Hindu society independent of the mainstream is highly improbable and problematic in the United States. Isolated attempts to create such a society here have been dismal failures. Witness for example the Hare Krishna movement. Assimilation of Hindus in the larger American mainstream is a foregone conclusion. Still, the Hindus will maintain their cultural identity in a manner similar to Chinese or Italians. They will have their Little Indias in New York, New Jersey, Chicago and other places with a considerable Indian population. These little Indias would be like Chinatowns and Little Italys that we find in most American cities. They cater primarily to the first-generation immigrants. For the larger society, they mostly serve commercial and culinary purposes. Their religious and cultural importance is minimal.

Hinduism as a phenomenon will not disappear in America. It will endure as an academic discipline at major universities. The younger Indians will continue to participate with gusto in Navratri Ras Garba or Bhangra, but that is because these festivals provide them an opportunity to dress up and dance. Their participation has very little do with the preservation of Hindu religion. Their observance of Hindu religious rituals, if any, would be perfunctory and without comprehension. However, as long as there is continuing immigration of Indians into the United States, the arriving first generations will continue to practice the religion in their homes and at temples. But their second and third generations would have moved on and assimilated into the American mainstream. The melting pot works!

—————————————————————————————

The Jews

We were Pharaoh’s slaves in Egypt

Wandering for decades

In the burning sands of the desert.

Then came the Lord

To take us out of Egypt

With a mighty hand

And said:

Out of all people that are on the face of the earth,

The Lord has chosen you to be

A people for his possession,

It was not because we were more in number

Than other people

But because the Lord loves us

Because we believe thus:

That God exists

That God has no corporeal aspect

That God is eternal

That God knows the actions of man

That God rewards those who keep the Torah and

Punishes those who transgress it.

The Lord has chosen us to be a people of his own.

Because we give more than what we receive

Because we keep our religion

Because we serve our God the lord no matter

Where we are on this earth or who we are

Because for us history is holy,

And memory a priceless treasure

Because we suffer and suffer

And still strive and survive.

We have proclaimed the lord to be our God

And the lord has proclaimed us to be his people.

e.mail : natgandhi@yahoo.com

![]()

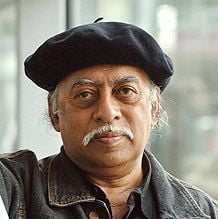

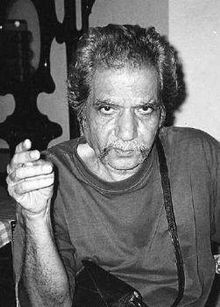

That like their contemporary poets Sadanand Rege, Grace, Arati Prabhu, Namdeo Dhasal and Narayan Surve, Chitre and Kolatkar too created a space for their sensibility and an independent readership in Marathi language. Although their poetry is loaded with the cultural references to Maharashtra like Dnyaneshwar, Tukaram, Jejuri, and Panhala, the Indian and Western ideologies emerged outside Maharashtra have also been assimilated in it and they are quite clear. Both these poets are the best examples of the influence of two hundred years encounter and hybridization of English and Marathi after Mardhekar. Mardhekar, Chitre and Kolatkar are the most significant Marathi poets of twentieth century who assimilated the Western literature and style but never forgot their native poetic tradition.

That like their contemporary poets Sadanand Rege, Grace, Arati Prabhu, Namdeo Dhasal and Narayan Surve, Chitre and Kolatkar too created a space for their sensibility and an independent readership in Marathi language. Although their poetry is loaded with the cultural references to Maharashtra like Dnyaneshwar, Tukaram, Jejuri, and Panhala, the Indian and Western ideologies emerged outside Maharashtra have also been assimilated in it and they are quite clear. Both these poets are the best examples of the influence of two hundred years encounter and hybridization of English and Marathi after Mardhekar. Mardhekar, Chitre and Kolatkar are the most significant Marathi poets of twentieth century who assimilated the Western literature and style but never forgot their native poetic tradition. It was in early nineteenth century the young teachers in Hindu College of Kolkata started the practice of using English to describe Indian scenario in poetry. With the inclusion of English language and literature in the curriculum of schools and colleges, this tendency got spread outside Kolkata too. Due to the English translation of his works as Rabindranath Tagore received the Nobel Prize for literature in the early twentieth century, the contemporary poetry was profusely translated from Indian languages into English. Emergence of modernity in literature in the post-Independence period stylistically breathed a fresh air into Indian English poetry. Recognition of English as an official language of India by Indian Constitution boosted up the tendency to prefer English language for creative writing though the writers lived in India. In the history of Indian poetry in English spanning over two hundred years the names of five to six poets are inevitably mentioned and after the publication of Jejuri in 1976 Arun Kolatkar is one of them. Moreover, Chitre's reputation has also been increasing in this canon. Publication of Nissim Ezekiel's anthology of poems A Time to Change (1952) has been considered as the beginning of modernity in Indian English poetry. During these four decades Ezekiel, Ramanujan, Kolatkar and Jayant Mahapatra are considered to have contributed substantially to this kind of poetry. Their poems are included in the university curriculum of several countries. And wherever English education has reached, these poets are known, may be at the introductory level, to the academic world of teachers and students. In recent times, Chitre's name is also getting associated with other prominent poets. Therefore, these two important Marathi poets of ours could have certainly been recognized as the significant poets in Indian English and therefore, significant Marathi poets too.

It was in early nineteenth century the young teachers in Hindu College of Kolkata started the practice of using English to describe Indian scenario in poetry. With the inclusion of English language and literature in the curriculum of schools and colleges, this tendency got spread outside Kolkata too. Due to the English translation of his works as Rabindranath Tagore received the Nobel Prize for literature in the early twentieth century, the contemporary poetry was profusely translated from Indian languages into English. Emergence of modernity in literature in the post-Independence period stylistically breathed a fresh air into Indian English poetry. Recognition of English as an official language of India by Indian Constitution boosted up the tendency to prefer English language for creative writing though the writers lived in India. In the history of Indian poetry in English spanning over two hundred years the names of five to six poets are inevitably mentioned and after the publication of Jejuri in 1976 Arun Kolatkar is one of them. Moreover, Chitre's reputation has also been increasing in this canon. Publication of Nissim Ezekiel's anthology of poems A Time to Change (1952) has been considered as the beginning of modernity in Indian English poetry. During these four decades Ezekiel, Ramanujan, Kolatkar and Jayant Mahapatra are considered to have contributed substantially to this kind of poetry. Their poems are included in the university curriculum of several countries. And wherever English education has reached, these poets are known, may be at the introductory level, to the academic world of teachers and students. In recent times, Chitre's name is also getting associated with other prominent poets. Therefore, these two important Marathi poets of ours could have certainly been recognized as the significant poets in Indian English and therefore, significant Marathi poets too.