વિદેશોમાં વસતા ગુજરાતીઓ માટેનો અંગ્રેજી શબ્દ જે હવે ગુજરાતી બની ગયો છે તે ડાયસ્પોરા મૂળ ગ્રીક શબ્દ ‘ડિસ્પેઈરીન' (ડાયસ્પર) પરથી આવ્યો છે. જેનો મતલબ થાય છે : વિખરાઈ જવું, ફેલાઈ જવું કે તિતર-બિતર થઈ જવું. હિબ્રુ બાઈબલનો જ્યારે ગ્રીકમાં અનુવાદ થયો ત્યારે ઈઝરાયલ-પેલેસ્ટાઈનની ભૂમિ પરથી યહૂદીઓના નિષ્કાસન માટે પહેલીવાર આ શબ્દનું પ્રયોજન થયેલું.

છેલ્લા બે દાયકાથી ડાયસ્પોરા શબ્દ યહૂદી નિષ્કાસનના દાયરામાંથી બહાર નીકળીને દેશાંતર કરતા મજદૂરો, ડબલ નાગરિકત્વ ધરાવતા લોકો, વિદેશી વિદ્યાર્થીઓ, બીજી-ત્રીજી-ચોથી પેઢીના વિદેશીઓ અને નસ્લીય વિરાસતમાં િહસ્સેદારી ધરાવતા લોકોની ઓળખાણ સુધી પહોંચ્યો છે. ડાયસ્પોરા ત્રણ પ્રકારના હોય છે: ઉત્પીડિત ડાયસ્પોરા, શ્રમિક ડાયસ્પોરા અને વ્યાપારી ડાયસ્પોરા.

ગુજરાતીઓ મૂળે ધંધાર્થે સ્થળાંતર કરતા હતા એટલે એમને યહૂદીઓ, જીપ્સીઓ પારસીઓ કે બૌદ્ધોના ઉત્પીડિત નિષ્કાસનનો અર્થ ખબર ન હોય તે સ્વભાવિક છે. હવે તો ઈમિગ્રાન્ટ અથવા અપ્રવાસી જેવો વધુ સભ્ય શબ્દ પણ વપરાશમાં આવી ગયો છે પરંતુ નરેન્દ્ર મોદી જેને ‘પહેલા ભારતીય પ્રવાસી' તરીકે ઓળખાવીને અમદાવાદમાં પ્રવાસી ભારતીયોનો મેળો યોજી ગયા તે મહાત્મા ગાંધી એક બીજો શબ્દ લઈને આવેલા : ગિરમીટિયા.

ગાંધીજી ‘પહેલા ભારતીય પ્રવાસી' હતા એવું કહેવામાં અને સાંભળવામાં સારું લાગે છે, પરંતુ બહુ ઓછા લોકોને ખબર હશે કે ગાંધીએ પોતાને ‘પહેલા ગિરમીટિયા' તરીકે ગણાવ્યા હતા. ગિરમીટિયા એટલે વેઠિયા મજદૂર. 1879માં ગુલામ ભારતમાં એક ઠેકા વ્યવસ્થા (ઈન્ડેચર િસસ્ટમ) તહત ભારતીય મજદૂરોને ફિજીનાં ખેત-બગીચાઓમાં કામ કરવા માટે લઈ જવામાં આવતા હતા. આ ઈન્ડેચર વ્યવસ્થામાં મજદૂરીના જે ‘એગ્રિમેન્ટ' પર એમના અંગૂઠા લેવામાં આવતા તે ‘એગ્રિમેન્ટ'ને આ અભણ-ગમાર ભારતીયો ‘ગિરમીટ' કહીને બોલાવતા હતા. 1916માં ફિજીમાં જ્યારે આ ઠેકેદારીનો અંત આવ્યો ત્યારે ત્યાં 60,965 ‘ગિરમીટિયા' પુરુષો, સ્ત્રીઓ અને બાળકો હતાં.

ગાંધીજી ‘પહેલા ભારતીય પ્રવાસી' હતા એવું કહેવામાં અને સાંભળવામાં સારું લાગે છે, પરંતુ બહુ ઓછા લોકોને ખબર હશે કે ગાંધીએ પોતાને ‘પહેલા ગિરમીટિયા' તરીકે ગણાવ્યા હતા. ગિરમીટિયા એટલે વેઠિયા મજદૂર. 1879માં ગુલામ ભારતમાં એક ઠેકા વ્યવસ્થા (ઈન્ડેચર િસસ્ટમ) તહત ભારતીય મજદૂરોને ફિજીનાં ખેત-બગીચાઓમાં કામ કરવા માટે લઈ જવામાં આવતા હતા. આ ઈન્ડેચર વ્યવસ્થામાં મજદૂરીના જે ‘એગ્રિમેન્ટ' પર એમના અંગૂઠા લેવામાં આવતા તે ‘એગ્રિમેન્ટ'ને આ અભણ-ગમાર ભારતીયો ‘ગિરમીટ' કહીને બોલાવતા હતા. 1916માં ફિજીમાં જ્યારે આ ઠેકેદારીનો અંત આવ્યો ત્યારે ત્યાં 60,965 ‘ગિરમીટિયા' પુરુષો, સ્ત્રીઓ અને બાળકો હતાં.

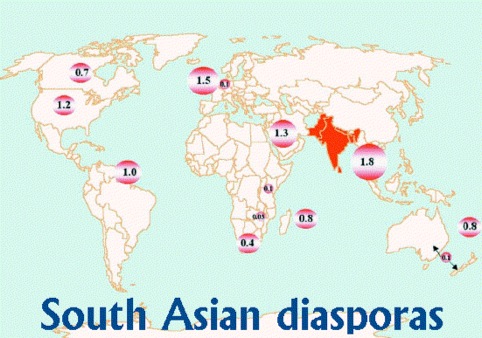

જે ફર્ક કેરીબિયન, મોરીશિયસ, ફિજી, મેલેશિયા અને આફ્રિકન બ્રિટિશ કોલોનીઓમાં મજદૂરી કરતા ભારતીયો અને યુએસ, યુકે, કેનેડા અને ઓસ્ટ્રેલિયા કામ કરતા ભારતીયો વચ્ચે છે તે જ ફર્ક ગિરમીટિયા અને ડાયસ્પોરા શબ્દ વચ્ચે છે. ડાયસ્પોરા અથવા અપ્રવાસીમાં મૂળ વતનનાં મૂળિયાં અભિપ્રેત છે જ્યારે ગિરમીટિયા એટલે સુખની શોધમાં બે-વતન થઈ ગયેલા લોકો. 1838માં બ્રિટને કાયદા મારફતે ગુલામી પ્રથા નાબૂદ કરી ત્યારે એમાંથી ઈસ્ટ ઈન્ડિયા કંપની હેઠળના પ્રદેશ બાકાત રખાયેલા.

ભારતમાં જ્યારે ઈસ્ટ ઈન્ડિયા કંપનીની સંપૂર્ણ હકૂમત સ્થપાઈ ત્યારે ભારતમાંથી મજદૂરોને વેઠિયા કામો માટે લઈ જવાની ઈન્ડેચર વ્યવસ્થા શરૂ થયેલી. ફિજીમાં જે ભારતીય મૂળના લોકો છે તે સંપૂર્ણ પણે આ ગિરમીટિયા પ્રથાને ‘આભારી' છે. 1838થી લઈને 1916 સુધી આ ગિરમીટિયા પ્રથા હેઠળ લગભગ 12 લાખ ભારતીયોને મોરીશિયસ, ગ્યુએના, ત્રિનિદાદ એન્ડ ટોબેગો, દક્ષિણ આફ્રિકા, ફ્રેન્ચ રિયુનિયન, સુરીનામ, જમૈકા અને ફિજીનાં ખેતરોમાં વેઠિયા મજદૂર તરીકે ઝુલસી દેવાયા હતા.

ઈન્ડેચર વ્યવસ્થાનો આ આખો કાળો ઇતિહાસ આજે જનસ્મૃિતમાંથી ભૂંસાઈ ગયો છે પરંતુ ગાંધીએ પ્રચલિત બનાવેલા ‘ગિરમીટિયા' શબ્દમાં એ સચવાઈ ગયો છે. 24 વર્ષની ઉંમરે ગાંધી ખુદ એક વર્ષના એગ્રિમેન્ટ પર બેિરસ્ટર તરીકે દક્ષિણ આફ્રિકા ગયા હતા. દક્ષિણ આફ્રિકાના શેઠ અબ્દુલાએ ગાંધીને બેરિસ્ટરની સેવા આપવા બોલાવેલા. એક જ અઠવાડિયામાં ગાંધીને કડવા અનુભવો થયા અને ત્યાંની પરિસ્થિતિનો ખ્યાલ આવી ગયો.

વકીલાત શરૂ કર્યાના બે-ચાર મહિનામાં જ ગાંધી પાસે બાલાસુંદરમ નામના તમિળ ભારતીય મજદૂરનો કેસ આવેલો જેને એના માલિકે સખત માર મારીને લોહીલુહાણ કરી નાખ્યો હતો અને બે દાંત પણ પડી ગયા હતા. ગાંધી એમની આત્મકથામાં લખે છે, ‘હું ગિરમીટિયાને લગતો કાયદો તપાસી ગયો. સામાન્ય નોકર જો નોકરી છોડે તો શેઠ તેના ઉપર દીવાની દાવો માંડી શકે. તેને ફોજદારીમાં ન લઈ જઈ શકે. ગિરમીટ અને સામાન્ય નોકરીમાં ઘણો ભેદ હતો. મુખ્ય ભેદ એ હતો કે ગિરમીટિયા શેઠને છોડે તો ફોજદારી ગુનો ગણાય ને તેને સારુ તેને કેદ ભોગવવી પડે. ગિરમીટિયો શેઠની મિલકત ગણાય. ગોરાને ત્યાં દાખલ થાય ત્યારે તેના માનાર્થે પાઘડી ઉતારે, બે હાથે સલામ ભરે તે બસ ન થાય.’

બીજા એક સ્થાને ગાંધી લખે છે, ‘જે કરાર કરીને પાંચ વર્ષની મજૂરી કરવા ગરીબ િહંદીઓ તે વેળા નાતાલ જતા તે કરાર અથવા ‘એગ્રિમેન્ટ'નું અપભ્રષ્ટ ગિરમીટ. આ ગિરમીટિયાને અંગ્રેજો ‘કુલી' તરીકે ઓળખે. ‘કુલી'ને બદલે ‘સામી' પણ કહે. ‘સામી' એટલે ઘણાં તામિળ નામોને છોડે આવતો ‘સ્વામી.' તેથી હું ‘કુલી બારિસ્ટર' જ કહેવાયો.’

ન્યૂયોર્ક ટાઈમ્સના સંપાદક જોસેફ લેલિવેલ્ડ એમની કિતાબ ‘ગ્રેટ સોલ : મહાત્મા ગાંધી એન્ડ હીઝ સ્ટ્રગલ વિથ ઈન્ડિયા'માં એવો દાવો કરે છે કે અંગ્રેજો દક્ષિણ આફ્રિકાના હિન્દુસ્તાની વેપારીઓ માટે પણ કુલી શબ્દનો પ્રયોગ કરતા હતા તે ગાંધીને પસંદ ન હતું અને એ અરસામાં ગિરમીટિયાઓ માટે આ શબ્દ વપરાય તેમાં એમને કંઈ વાંધાજનક લાગતું ન હતું. એ વખતે એ હિન્દુસ્તાની વેપારીઓના જ પ્રવક્તા હતા. 1913માં જોહાનિસબર્ગમાં ગોરા ખાણ કામદારોએ હિંસાત્મક હડતાળ પાડી તે દિવસોમાં ગાંધીજીને ગિરમીટિયાઓ માટે ‘કંઈક' કરવાના વિચારો આવેલા એવું એમના સચિવ પ્યારેલાલ નોંધે છે.

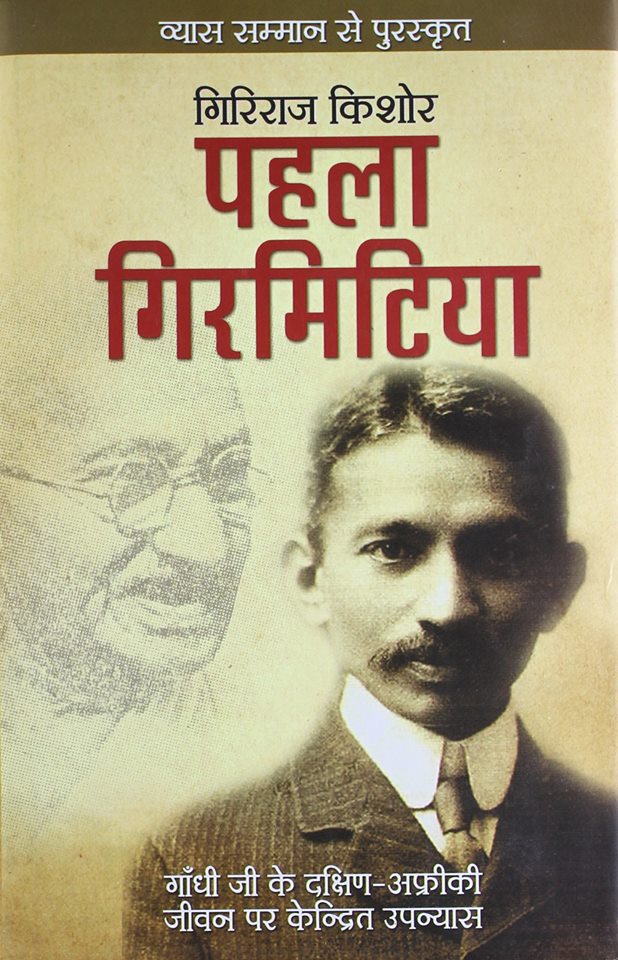

ગાંધીએ જ્યારે હિન્દુસ્તાનીઓ માટે લડત શરૂ કરી ત્યારે પોતાને પહેલા ગિરમીટ તરીકે ઓળખાવ્યા હતા. ગાંધી લખે છે, ‘ગીરમીટ એ અડધી ગુલામી જ છે.' િહન્દીમાં ગિરિરાજ કિશોરે ગાંધી ચરિત્ર લખ્યું છે તેનું શીર્ષક ‘પહેલા ગિરમીયા' છે. ગુજરાતીમાં મોહન દાંડીકરે નવજીવન પ્રકાશન માટે ‘પહેલો ગિરમીટિયો’ નામથી અનુવાદ કર્યો છે.

આ કદાચ પ્રથમ વાર્તા છે જેમાં મોહનદાસથી મહાત્મા સુધીની સફર કહાનીનુમા રૂપે પેશ કરવામાં આવી છે. એમાં નાયક મોહનદાસ ગિરમીટિયા છે જે રોજી-રોટીની તલાશમાં દક્ષિણ આફ્રિકા ગયો છે. મોહનદાસ પહેલો ગિરમીટિયો હતો જે બેરિસ્ટર પણ હતો અને કુલી પણ.

ગિરિરાજ કિશોર આ કહાનીની પ્રસ્તાવવામાં લખે છે, ‘આ કહાનીનું મુખ્ય પાત્ર મોહનદાસ એટલી જ સામાન્ય વ્યક્તિ છે જેટલી મારા-તમારા જેવી હોય છે. એ ન તો ચાંદીની ચમચી સાથે પેદા થયો હતો કે ન તો સોનાના મુગટ સાથે. પત્નીનાં ઘરેણાં વેચીને લંડન બાર-એટ-લો કરવા ગયો હતો. પિતા મરી ગયા હતા, કાકાએ બહાનું બતાવીને ઠેંગો બતાવ્યો હતો, મોટા ભાઈની પોતાની મર્યાદાઓ હતી. જ્યારે બેરિસ્ટર બનીને પાછો આવ્યો તો બેરોજગાર રહી ગયો. મોટા ભાઈના માથે પડ્યો. કોર્ટોનાં ચક્કરમાં અનૈતિકતા અને વ્યક્તિગત નૈતિકતાના સંઘર્ષમાં ફસાઈ ગયો. બોલતાં ન આવડે એટલે કેસ હારી જાય. થોડી ઘણી કમાણી મોટાભાઈના વકીલ દોસ્તોના ક્લાયન્ટો માટેની લખાપટ્ટીમાંથી થતી હતી અને એમાંથી અડધો હિસ્સો વકીલ લઈ લેતો. શોષણની આ રીતથી મોહનદાસ પરેશાન હતા. પરિણામે દેશના હજારો ગરીબ અભણ, બેરોજગાર મજદૂરોની જેમ એ બેરિસ્ટરને પણ રોજી-રોટી કમાવા માટે એક વર્ષના ગિરમીટ (એગ્રિમેન્ટ) પર દક્ષિણ આફ્રિકા જવું પડ્યું.'

ગયા મે મહિનામાં ફિજીમાં ગિરમીટિયાઓના આગમનને 180 વર્ષ પૂરાં થયાં ત્યારે આંતરરાષ્ટ્રીય ગિરમીટ દિવસ 2014નું આયોજન કરવામાં આવ્યું હતું જેમાં ગિરમીટિયાઓના અનેક વારસદારો, જે આજે પ્રતિષ્ઠિત જિંદગી જીવી રહ્યા છે, તેમનું સન્માન કરવામાં આવ્યું હતું. આ એક પ્રકારનું પ્રવાસી ભારતીય સંમેલન જ હતું.

સવાલ : ગાંધીજી જીવતા હોત તો પ્રવાસી ભારતીય દિવસને તેમણે ગિરમીટિયા ભારતીય દિવસ ગણ્યો હોત?

… સોચો.

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=891324457584565&set=a.105033859546966.2361.100001210570216&type=1&theater

![]()

Bead Bai (ખોટા મોતી ના સાચા વેપારી) by Sultan Somjee

Bead Bai (ખોટા મોતી ના સાચા વેપારી) by Sultan Somjee Basically, it is about the settlement of the Satpanth Ismaili Khoja community in East Africa with roots in the princely state of Kathiawar in British India, but Somjee has skilfully contextualised the tales of their arrival and venture into the hinterland with the art and craft of native bead making. He is an ethnographer by academic training and in this extraordinarily ambitious work he has used his learning and professional expertise, gained over many years` field work in Kenya, to perfection.

Basically, it is about the settlement of the Satpanth Ismaili Khoja community in East Africa with roots in the princely state of Kathiawar in British India, but Somjee has skilfully contextualised the tales of their arrival and venture into the hinterland with the art and craft of native bead making. He is an ethnographer by academic training and in this extraordinarily ambitious work he has used his learning and professional expertise, gained over many years` field work in Kenya, to perfection. કાયમી વસવાટ માટે કેનેડા માઈગ્રેટ થયો ત્યારે સેટલમેન્ટ પ્રોસેસના ભાગરૂપે કેનેડિયન હ્યુમન રિસોર્સીઝ ડિપાર્ટમેન્ટ દ્વારા ઇમિગ્રન્ટસ માટે ચાલતા વર્કશોપમાં ભાગ લીધેલો. વર્કશોપમાં એક પ્રશ્ન પૂછાયેલો, "વ્હાય યુ કેઈમ ટુ કેનેડા ?" મારી સાથે ભાગ લઈ રહેલ મોટા ભાગનાનો જવાબ હતો …….. "ફોર એ બેટર લાઈફ !" હમણાં જ અંગ્રેજી લેખક વિજય જોશીનો આર્ટિકલ, A Perpetual Sojourn વાંચ્યો. એક ઇમિગ્રન્ટ તરીકે વતનથી જોજનો દૂર વિદેશમાં સ્થળાંતર થઈ સ્થાપિત થયાનો આનંદ અને વતનથી વિસ્થાપિત થયાની વેદનાની મિશ્ર લાગણીઓ વર્ણવતો તેમનો લેખ હૃદય સ્પર્શી ગયો. "ડાયસ્પોરા"ની મૂળ વાતમાં યહૂદી પ્રજાનું મિસરની ગુલામીમાંથી મુક્ત થવા અન્ય સ્થળે વસવાટ કરવા જવાના વર્ણનમાં પણ આજ કથા-વ્યથા છુપાયેલી છે.

કાયમી વસવાટ માટે કેનેડા માઈગ્રેટ થયો ત્યારે સેટલમેન્ટ પ્રોસેસના ભાગરૂપે કેનેડિયન હ્યુમન રિસોર્સીઝ ડિપાર્ટમેન્ટ દ્વારા ઇમિગ્રન્ટસ માટે ચાલતા વર્કશોપમાં ભાગ લીધેલો. વર્કશોપમાં એક પ્રશ્ન પૂછાયેલો, "વ્હાય યુ કેઈમ ટુ કેનેડા ?" મારી સાથે ભાગ લઈ રહેલ મોટા ભાગનાનો જવાબ હતો …….. "ફોર એ બેટર લાઈફ !" હમણાં જ અંગ્રેજી લેખક વિજય જોશીનો આર્ટિકલ, A Perpetual Sojourn વાંચ્યો. એક ઇમિગ્રન્ટ તરીકે વતનથી જોજનો દૂર વિદેશમાં સ્થળાંતર થઈ સ્થાપિત થયાનો આનંદ અને વતનથી વિસ્થાપિત થયાની વેદનાની મિશ્ર લાગણીઓ વર્ણવતો તેમનો લેખ હૃદય સ્પર્શી ગયો. "ડાયસ્પોરા"ની મૂળ વાતમાં યહૂદી પ્રજાનું મિસરની ગુલામીમાંથી મુક્ત થવા અન્ય સ્થળે વસવાટ કરવા જવાના વર્ણનમાં પણ આજ કથા-વ્યથા છુપાયેલી છે.